As coursework for my Masters in Photography, this is a presentation on my current practice and my Hidden Corners project.

Tag: Coursework

Me, my practice, and I.

My practice is an exploration of place, especially the interaction of the human, the vegetal and the geological. With a background in film and writing, I’m interested in the possibilities of sequencing and incorporating text, and since beginning this Masters, I have developed a strong appreciation of the photobook as a means to explore and express places. My critical background draws on work in film and literature and includes a keen interest in cultural geography and environmental psychology, as well as critics Rebecca Solnit, Liz Wells and Jacky Bowring. The focus of my work, within the restrictions of the CV-19 pandemic, is an area of registered common land close to my home in Exeter, the Pebblebed Heaths. I’ve been photographing it and learning about it for several years and am getting to know those connected with it both personally and for their livelihoods.

CRJ Task W8: Exhibiting my work

Into the Woods: Trees in Photography was a small exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum which opened in late 2017. It contained the work of 40 photographers from throughout the history of photography, some chosen from the V&A archives, others from those of the RPS. Photographers included Crystal Lebas, Abbas Kairostami, Stephen Shore, Alfred Steiglitz, Alvin Langdon Coburn, Mitch Epstein, Paul Strand, Robert Frank, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Edward Steichen, Wolfgang Tilmans, Lee Friedlander, Jean-Eugen-Auguste Atget, Jem Southam, Simone Nieweg, Paul Hart, John Davies, Robert Adams, Ansel Adams, Ingrid Pollard, Paul Hart, Paul Hill and Fay Godwin.

It’s interesting that many of these names have become very familiar to me and influenced my work, although the majority I’d not heard of at the time. The exhibition intended to demonstrate the enduring fascination with and diversity of responses to the tree as aesthetic object and was expanded into a book published in 2019 by Thames & Hudson.

Despite its impressive roster of names, Into the Woods appears to have been almost entirely overlooked by the critics. This is perhaps due its size, or perhaps that such a theme wasn’t considered worthy of critical attention. As such, only The Times‘s Nancy Durrant took the trouble to do more than provide an enthusiastic gloss over the bare details. Her review focusses on the sensory experience of being amongst this subject, and is appreciative of the formal and technical excellence and diversity of the selection, making no attempt to draw out any kind of political statement from the exhibition. This, to me, is entirely the point: politics are glimpsed – environmentalism via Robert Adams, race via Ingrid Pollard, for example – but the tree remains the focus of the exhibition. It does not use trees to talk about other things.

I also take pictures of trees. Of course, my work would never appear in such an exhibition because I’m not even a paid photographer, let alone a celebrated one. But I do have my own relationship to trees, my own way of using them. I’m especially interested in the eerie, monstrous shadows trees cast when they’re bare, and the ways these completely alter their environments.

I’ve also been through periods of photographing urban trees at night as they interact with artificial lighting from buildings and street lights.

Neither of these ways of looking at trees was represented in the exhibition, which sometimes was a little too reassuring, and maybe if I got really good at what I did, one would have found a place here.

Barnes, M. 2019. Into the Woods: Trees in Photography. London: Thames & Hudson.

Durran, N. 2017. Come where you can see the art for the trees. The Times. December 12.

Politics vs. aesthetics

It might seem like a bit of a cheat, but I’m reposting a forum post here, as I can’t think of anything more pertinent to where I’m at in my practice right now. This week has been absolutely on the money for me.

This week’s topic could not have come at a more apt moment for my work. Following feedback from both Jesse and Steph at last week’s symposium, it’s clear that my work is currently weighted too heavily towards aesthetics at the expense of communication. This is something I’ve been wrangling with for some time, as on the one hand, I get great pleasure and satisfaction from the formal process of composing a well-balanced and executed image, while on the other, wishing to convey the deep politics and complex histories of registered common land. These aren’t incompatible, but this demonstrates how uneasy is the partnership between aesthetics and message. I’ll get to my images later in this post.

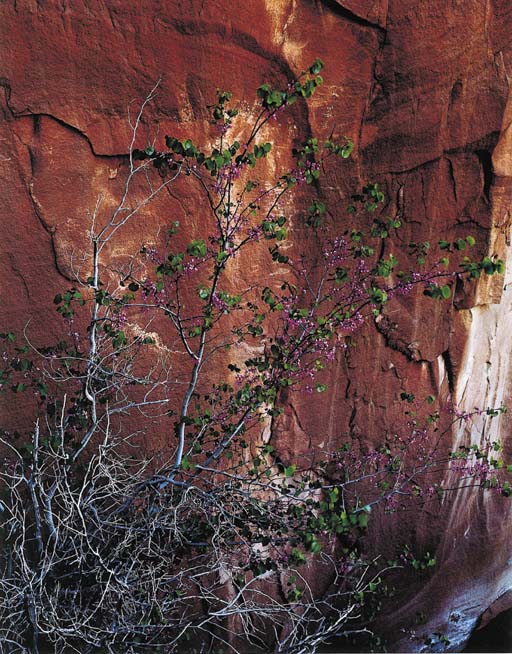

I’m looking at two interconnected bodies of work: first, Elliot Porter’s The Place No-one Knew (1963). Porter was an associate of Ansel Adams, a fellow campaigner in The Sierra Club, and a trailblazer in the use of colour. I’m a great admirer of his work on a formal and technical level, and because his work powerfully communicates sense of place through abstracts, something central to my own approach. He’s been a big influence on my work.

The Place No-one Knew was created to raise awareness of the imminent flooding of Glen Canyon, Utah, to create Lake Powell. A copy was sent to the president. The effort failed in the short term, but as so often, the awareness raised helped mitigate and slow down the ongoing flooding of the US South West’s canyonland for hydroelectric schemes.

So far so good. However, Porter, like Adams, was deeply influenced by a very white middle-class form of conservationism – indeed, this is still a huge problem for the conservation movement, as demonstrated by the paucity of diversity in Extinction Rebellion – although this an issue specifically being addressed within this dynamic and vital movement. Porter’s effort thus spoke to a specific audience – and on behalf of others without consulting with them first. Though remote, Glen Canyon was, in fact, already well known to hikers, fishermen, and a small local population that included Native Americans. This group, while appreciating Porter’s efforts, were nevertheless furious, not least at the name of the book.

So we have Porter’s unique vision. It IS glorious, but it’s highly individualistic, and that becomes a problem when it’s married to politics. The work is, frankly, a bit TOO glorious. It might evoke a sense of place, but it does not evoke a sense of uncertainty or danger. The images are, in other words, and in spite of the accompanying essay, devoid of context (something picked up on by both Jesse and Steph in some of my own). In other words, Elliot has let aesthetics get in the way of his message. The very beauty communicated so effectively and intended to instil concern and galvanise action, ends up soothing, reassuring. Glen Canyon becomes no place at all, just another site for Porter’s work, and in that case, this suggests an abundance of glorious places for glorious work. The aesthetics anesthetise.

Drowned River: The Death & Rebirth of Glen Canyon on the Colorado is the second project resulting from a collaboration between Mark Klett, Byron Wolfe and environmentalist, journalist and art critic Rebecca Solnit. It takes Porter’s work as a starting point, respectfully but critically, and uses it to explore Lake Powell as the climate-change-driven receding water levels reveal Glen Canyon once more. The work is no less aesthetically glorious. The colours are more mute, but that’s more to do with the different technologies and tastes of each era. Klett and Byron pick up on abstracts, just like Porter, and their framing is clearly influenced by the original work. It is a celebration of a landscape and a brilliantly-executed communication of place, even if it’s quite a weird place.

Unlike the standard essay-then-images of Porter’s work, Solnit’s essay flows through the images, creating a dialogue with them, providing the contexts of climate change, critiquing Porter, but also revelling in the experience of being out exploring. There being a notable lack of prominent female ‘landscape’ photographers, having a female voice is part of the strength of the project. Both images and text situate the collaborators throughout the work, and this enhanced subjectivity, and that this is a collaboration both disrupt the individualistic vision of The Place No-one Knew. In doing this, the viewer is encouraged to develop their own relationship with the place; the observers are in this way part of what the viewer is able to observe, rather than Porter’s direct communication of a unique viewpoint. This engagement helps develop agency, and an active viewer is more likely to feel prompted to act than a passive one. The socio-political and historic context of place is also communicated through the images, though without didacticism. Hence litter, cracked mud and vapour trails are stark reminders of environmental destruction, while abandoned picnic tables, boats and closure signage remind of the cost of the receding waters to local communities. In this way, the viewer gets the impression of being a fellow traveller to the leading edge of catastrophic climate change and the novel landscapes it is already creating.

I took on board what was said to me by Jesse and Steph, and with this in mind, went looking more specifically for the military traces at the Pebblebed Heaths. Aesthetics have remained important – and there are here images taken just to communicate a sense of place – but a meticulous, critical eye keen to communicate context was also something I had in mind. I’m still sorting through these images, but below are a few.

Klett, M., Solnit, R., & Wolfe, B. 2018. Drowned River: The Death & Rebirth of Glen Canyon on the Colorado. Santa Fe: Radius Books.

Porter, Elliot. 1963. The Place No-one Knew. San Francisco: The Sierra Club.

Informing Contexts W7 Task: Preparing for tutorials

Working towards my critical review, I’m answering the following questions posed on my current module.

How do you critically articulate the intent of your photographic practice (verbally or in writing)?

This is something that’s radically changed over the past year. I’ve spent much of my academic life clearly demarking my critical writing from my creative output. I think this has been a mistake and a lost opportunity to create something much more coherent – and potent. Studying the essay film, and the essay form more generally, has been the catalyst for this. Essayism permits a hybrid intermixing of styles: according to Aldous Huxley, a formidable essayist, describes this ‘personal investigation’ as existing between three poles: ‘…the personal and the autobiographical; …the objective, the factual, the concrete-particular; and…the abstract-universal…The most richly satisfying essays are those which make the best…of all three’ (p. 84). Curiously, this very closely mirrors Robert Adams’ discussion of landscape photography: ‘Landscape pictures can offer us…three verities – geography, autobiography, and metaphor. Geography is, if taken alone, sometimes boring, autobiography is frequently trivial, and metaphor can be dubious’ (p. 14). Also central to essayism is a tentativeness, an incompleteness, a depiction of the act of thinking through which invites rather than closes down debate (Rascaroli, 2017). After many years ignoring my emotive, personal responses to the world in favour of the cool logic of the critical, it has been a joy to return to subjective response and use that as the starting point for criticism, rather than treat it is an embarrassing burden. It has returned critical activity to the realm of play.

How is your photographic practice critically, visually and contextually informed?

My response here is connected to the previous one. When I head out with my camera, I usually have in mind things I want to explore and think through; my photography, from the planning stage to the sequencing, is itself an act of criticism. For example, on my last shoot, I wanted to explore the military ruins on East Budleigh Common, and consider how they have been reappropriated by conflicting users – graffitti artists and The Bat Conservation Trust – while remaining under the ownership of the Army. Doing so, I thought through ideas of impermanence, conflict, subversion, and also felt the weight of distance between my own artistic activity and that of the graffitti artists. Was I being voyeuristic capturing their decaying art, or was I responded to it and extending it artistically? Probably both.

When I go out, I immerse myself in a place: this is something referred to by other landscape photographers such as Ansel Adams, but I suspect is also commonly found among street photographers. To an extent, I lose myself in experience, allow my surroundings to act on me and coax responses from me: the external world has an agency which I believe the apparently one-way model of ‘the gaze’ does not consider. Rather, there is a dialogue between myself and the external world: through my photographs, I shape it, while it in turn shapes me. I test out my ideologies by identifying subjects that allow me to consider them and see what comes back. I rarely take pictures that I could have foreseen. Finding expression for this blurring of boundaries between self and environment is a central concern of cultural geographers who study place and landscapes by drawing on phenomenology, such as John Wylie. It has been foundational to my filmmaking for the past year and, without my quite realising it, has shaped my photographic practice similarly.

It’s hard to consider how my practice is visually informed. It’s rarely a conscious choice. Certain photographers create work that chimes with my own intentions and I immerse myself in the experience they communicate. Increasingly, I am finding the means to evaluate such work critically, as evidenced throughout this journal, to understand my responses to it, and to consider what I believe is being communicated. It’s rare that I take a shot that quotes another photographer consciously: I have a ‘Fay Godwin’ view of a tree that I’m very fond of shooting under different atmospheric conditions, and I’ll sometimes square off a shot looking down at surfaces in a vaguely Stephen Shore-ish way. And I have always taking shots which I believe have picturesque or sublime qualities; the only difference is that now I understand the heritage of these.

How do you reflect on your photographic practice (e.g. editing / research etc) in order to progress it (consider successful and less successful work)?

I reflect in three ways. Firstly, I expose myself to photographers whose work I believe I can learn from, especially work which I can see is reaching for similar ideas or effects but which does it with vastly more sophistication and polish. Secondly, I go out and take shots. Again and again and again. I try new things, I develop and refine old things. Lastly, I review my work and consider it first on its formal and technical merits, and then I will consider if it is communicating or suggesting something worth caring about – an idea, a mood, a narrative.

In what professional / viewing context should your work be seen in. why?

I’d like to see my work in galleries, photobooks, because that’s where the photographs I like and aspire to are found. I’ve an idea to work up my commons project into a text-led book, but this is still in the development stage. I don’t think I’m yet at a point – or if I’ll ever get to a point – where any of this is possible. Besides, I wouldn’t even know where to begin. I’ve no idea who’d care enough about my work to help make that happen. This is probably a question best left unanswered until after the next module. Frankly, it intimidates the hell out of my. Why should anybody care about my work when there are so many great photographers out there still struggling to get noticed?

Adams, R. 1996. Beauty in Photography (Second Edition). NYC: Aperture.

Huxley, A. 2017. Preface to The Collected Essays of Aldous Huxley. In N. Alter & T. Corrigan (eds.) Essays on The Essay Film. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 83-85.

Rascaroli, L. 2017. How The Essay Film Thinks. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wylie, J. Landscape. 2007. London: Routledge.

A first encounter with Ranciere.

I’ve been using Bakhtin’s theory of dialogism for the past decade, first in studying and writing the novel, and then in studying and making film. Although Bakhtin’s work began in theorising the visual arts, his mature work focusses on literature (Bakhtin, 1984). As film is to a large extent a predominantly narrative form, dialogism can be transferred with only a small amount of adaptation. Using his theories to research visual art, however, can present obstacles where the work is not explicitly narrative in nature. Works do exist (e.g. Haynes, 2009), and I will make use of these in due course.

What appeals to me about Bakhtin is that he locates the artist as embedded socially, influenced by and in turn influencing the discourses, particularly those carried in language, in which they are immersed. Specifically, Bakhtin grants the artist, and indeed all people, agency in evaluating, responding to and articulating discourse; he considers this the fundamental activity in the creation of identity. This agency permits a more fluid, complex and subtle application of ways in which discourse constitutes socially and has been influential in shaping periods of post-colonial and feminist thought. However, while both lexical and symbolic language is constituted through photography, as articulated thoroughly through theoretical focus on semiotics, I am presently more interested in how aesthetic style is socially embedded rather than simply individualistic. By this, I mean not simply the historic artistic pedigree of style, but how style engages with and is shaped by society in a wider sense.

I was thus enthused to come across the work of Ranciere in the context of photography. Ranciere’s theories of artistic regimes – distinct but overlapping historical movements that shape but create problems for artists – connects aesthetics to politics, philosophy and community (Deranty, 2010). Like Bakhtin, Ranciere argues that the artist struggles with the influences of their regimes, especially where different elements appear contradictory, and their art is an attempt at reconciliation. He also refutes different artistic media as discrete and hermetic worlds but sees them as different iterations of and responses to these regimes, something that chimes with my own outlook having practiced in several different art forms and my wish to combine these in my work. Ranciere’s theorising of montage is also going to be relevant here and worthy of further study.

Ranciere argues that, in the wake of the c.18threvolutions and Romanticism, which he links, the present regime is that of the aesthetic, whereby the expressivity of language in its own right becomes the dominant focus of artistic activity, rather than as simply a vehicle for representation. It’s important to note that Ranciere does not argue in absolute binary terms, and that different regimes co-exist and cross-fertilise; the representative regime is still a major influence on art made up to the present. This way of understanding my own practice begins to answer my problems with the gaze, which appears to me to be too ideologically limited a definition of the practice of photography.

Like Bakhtin’s identification of polyphony in the novels of Dostoevsky, Ranciere argues that the aesthetic regime makes possible a radical equality of voices whereby no subject matter or means of expression is invalid in the creation of art, and he traces c.20thexpressions of this such as pop art and postmodernism back to Romanticism. Of particular interest to my practice is Ranciere’s identification of the aesthetic regime as making possible direct artistic ‘expressivity’ of the world’s raw material, rather than or in addition to, as with the representational regime, the world as a symbol. I’m very much interested in expressing palpable, experienced presence through my photography – and film – while being mindful of symbolic meaning. This is a very good starting point for me to begin to reconcile these seemingly paradoxical elements; indeed, Ranciere specifically considers, critiques and develops Barthes’ model of the punctum and stadium (1993) which articulates a related binary in a quite distinct way.

Having only recently read Ranciere, I am still digesting it. However, I will report back at a later date how this is becoming relevant to my practice.

Bakhtin, M. M. 1984. Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Barthes, R. Camera Lucida. 1993. London: Vintage Classics.

Deranty, J. (ed.) 2010. Jacques Ranciere: Key Concepts. London: Routlege.

Haynes, D. J. 2009. Bakhtin and the Visual Arts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Informing Contexts W4: CRJ Task

At present, the intent of my practice is to develop a personal aesthetic, emotional and political relationship with the places which I visit by interacting with them by walking and photographing. My technical strategy is to walk around a site in a semi-organised manner, having plotted an idea for a route, and then allowing myself to become distracted and deviate from this as I come across places, objects and views which attract my attention. I photograph these on the fly. I follow personal preferences for photographing traces of human and animal activity, abstracts such as reflections and organic patterns, viewpoints, and idiosyncratic details such as radio masts and ruins. I use a 24-70mm lens to accommodate these different types of shot and have recently upgraded my camera to one with a larger sensor to better record natural textures such as bracken, leaves and heather.

At present, these are intended to communicate the sense of place as it appears to me. I shoot a large number of photographs and present only the best. These communicate sense of place effectively to others, judging from their feedback. As such, and at present, my chosen strategies are successful. As the project is still in its explorative stage, once refined, the intention will become more defined and the strategies narrowed accordingly. Images will also sit with text, which I have not begun to include as yet.

Informing Contexts W3 Task: A Constructed Photograph.

While I can appreciate manipulated photography, I rarely find a connection to it. Gaudrillot-Roy’s ongoing series is a rare example. His work doesn’t so much capture the eeriness of the mundane, as coaxes it out. There’s always something slightly eerie about quiet streets in the dead of night, a sense of the unreal, and Gaudrillot-Roy makes this manifest by stripping away the buildings and adding new details, while maintaining a superlative command of line, tone and colour. The images are like pages from a children’s fantasy book, and defy any kind of logic, but rather communicate in an emotive, imaginative way.

They might be playful, but there’s also a sense of anxiety, even terror – where have all the people gone to? Am I, the viewer, all alone in this strange world? Has there been a strange apocalypse, or am I seeing the world as it always has been, the world of families and jobs and bars an illusion I’m seeing through for the first time?

A social message could be drawn from this, but I suspect this is of lesser importance to the image than the communication of mood and the injunction to imagine. Certainly, this is the impression one gets from Gaudrillot-Roy’s commentary.

This week’s reflection tasks asks me to position my practice in relationship to this work. I cannot. I have neither the technical skills nor the inclination to adopt such strategies. As a photographer also interested in the eerie, however, it is interesting to see how a photograph can be used as a starting point for further development.

http://www.zachariegaudrillot-roy.com/en/portfolio-20289-0-40-facades-3.html

Journal Summary W2

My practice hasn’t really moved on since last week, and I haven’t found this week’s learning, although interesting, especially relevant. I’m not much interested in questions of truth or the peculiar nature of the photographic medium. Rather, I’m interested in photography as a way by which I can engage with and interpret the world can reveal a set of truths – provisional ones of course, as truth is always thus. I’m interested in photography as methodology.

Through being forced to consider communicating meaning, I find I’ve come back to where I was in later Spring last year, beginning to understand the essay form in documentary film – a thinking through of ideas, a gleaning and sifting of materials, a self-conscious testing out of notions and practices. This is why this week’s materials haven’t been terribly productive for me – everything is much too, albeit necessarily, up in the air. Ask me these questions again some time, and I’ll most likely have some answers. I’m using my camera as a form of thinking, so let me think some more and I’ll get back to you.

As for contexts – I’m thinking book, or possibly article, or possibly both. I want my work to exist in dialogue with text, certainly, and I’m keen to escape the increasingly oppressive omnipresence of the screen somehow. I’m also keen to use sensory ethnography as a methodology, and some of the opportunities opening out at the Pebblebed Heaths will lend themselves to this. I continue to explore geography in connection with this, and am also learning about landscape art more broadly. But it’s all very early days, I don’t have anything specific to say beyond that.

What, if any, sort of truth do you think photography can or might offer us?

I’ve looked at the idea of truth from a number of angles over the years. I’ve looked at realism in the novel, taking in, ostensibly, foundational realists such as Dickens and subversive historiographic metafictionalists such as Rushdie. My conclusion was that the novel, whether realist or not, aims to represent an ironic impression of truth in which the author is always implicit, whether intentionally so or not. I’ve looked at different models of documentary truth, a battlefield of authenticity still arguing with itself over whether the fly-on-the-wall objectivity of ‘direct’ cinema is ever possible – or even relevant in a postmodern age. My own conclusion is that any documentary ‘truth claims’ are found not in the material itself, but in a contract, whether explicit or implicit, made with the viewer as to the relationship to truth being presented. Through market research and psychology I’ve studied the age-old antagonism between qualitative and quantitative data and thus the merits and problems with empiricism – and psychology’s current and growing ‘cultural turn’ through social constructivism. Crucially, from the perspective of truth and photography, it’s worth noting that even a basic understanding of cognitive psychology utterly destabilises any notion of ever being able to directly perceive an objective reality through the sense (contemporary physics increasingly proposes that there is no such thing anyway). Indeed, the ‘naturalness’ which we assume is inherent in looking at a flat image is anything but, as demonstrated by the length of time it takes blind people to ‘learn’ to interpret them should their sight be restored.

In other words, ‘truth’ is a slippery, ideologically loaded term. There is, of course, a cultural expectation that persists even in the era of deep-fakes, that photographs tell the truth, even if it’s only the faintest echo of a truth. It’s my belief that this isn’t something inherent in the medium itself, but rather something that has grown up alongside it in the ways it has been deployed to support scientific, legal, journalistic assertions about ‘truth’ in the specific era it did. I would thus caution that denoting photography as being, or being believed to be, more truthful than any other form of image-making – including textual descriptions of images – is thus culturally-specific. In an era saturated with photographs, it’s difficult but worthwhile considering that painted portraits, for example, were as much freighted with ‘truth’ prior to photography’s invention as photographic portraits were afterwards. So, my answer to the question ‘what kind of truth can photography offer us’ would be: any kind of truth one feels like making a claim for – so long as one sets the terms of that claim or understands the terms implied in the contexts in which one permits one’s work to be viewed – and then fulfils them.

I believe the photograph is different to other forms of visual representation, though I believe the degree of difference varies with the process and form of the image. Take, for example, evidentiary photographs such as passport photos and compare them with one of the few remaining circumstances where drawing is evidentiary – the courtroom. Both are perceived to be highly objective, and whether forced facial expressions, flash lighting, or use of shading or pencil colour, these are accepted as elements of each medium which transcribes a ‘reality’ onto a flat surface for scrutiny. In both cases, light has entered through a lens – the photo booth’s, the courtroom artist’s eye – and a process has been initiated for this to happen. In neither case is the implicit subjectivity of authorship considered relevant. And yet in the courtroom drawing, the artist is omnipresent. We know that this artist was sitting in this chair, saw this scene with their own eyes, and used their hands to make those lines. In a photograph, regardless of how objective or subjective it is viewed as or intended to be, there is an implicit surplus, however slight, which escapes the control of the artist: to some extent, the image that we see was recorded by a machine and no conscious decision was made by anyone about it: it was a direct relationship between a primed mechanical process and the light available to it. However much the process or the available light might have been manipulated by human agency, there will always be a surplus which escapes.

Take, for example, Warhol’s screen-prints: Warhol is understood as ‘author’ of these images (even though he frequently didn’t make the prints himself). They are exhibited as ‘Warhols’ and the identity of the original photographer negated: the process is overtly one of paint and paper and the human hand is everywhere present. The Marilyn photos themselves are understood as fictionalised to a certain extent even before Warhol’s intervention – as icon of beauty and gender, she has a cultural meaning that Warhol accentuates – and understood as staged glamour shots. And yet there persists, deliberately, a mechanical surplus which escapes any intention to interpreted, and the screen prints are careful to retain the faintest echo of this: they remain photographs. Had this been a painting of a photograph, however faithful, the mechanical chain would have been broken – although, and this is crucial, the painting would have to be ‘understood’ as a painting, and not a photograph. It is this ‘understanding’ of the photograph’s unique quality of mechanical ‘surplus’ on which rests the cultural meanings of photographic ‘truth’ and makes possible the myriad strategies and games of communicating the photographic image.

Even in the era of deep-fakes, I don’t believe any photograph can escape questions of veracity – even if it positions itself to argue against this, whether tableau, digitally enhanced, in the gallery or used for publicity. Public scepticism might be more attuned to it, but there remains a contract of truth between photographer and viewer, even if that truth is as basic as the photograph being a photograph and not another medium.

You must be logged in to post a comment.