Gleaning and the essayistic.

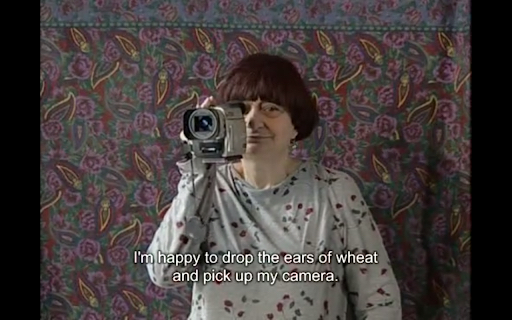

In The Gleaners & I (2000), director Agnes Varda makes the comparison between gleaning and making art. This popular and influential documentary was Varda’s first using the versatility of digital video which for the first time let her make films unencumbered by a film crew. The film takes for its subject the variety of people who glean, whether for rejected potatoes, unharvested olives, discarded furniture, or unsold market produce. Varda makes clear the difference between those who glean because they are poor and those who glean because they value the activity, saying of her own ‘artistic gleaning…you pick ideas, you pick images, you pick emotions from other people, and then you make it into a film’ (2001). Tellingly, having found this out about herself, Varda continued her gleaning to create installation art, a completely new but entirely logical direction for her work.

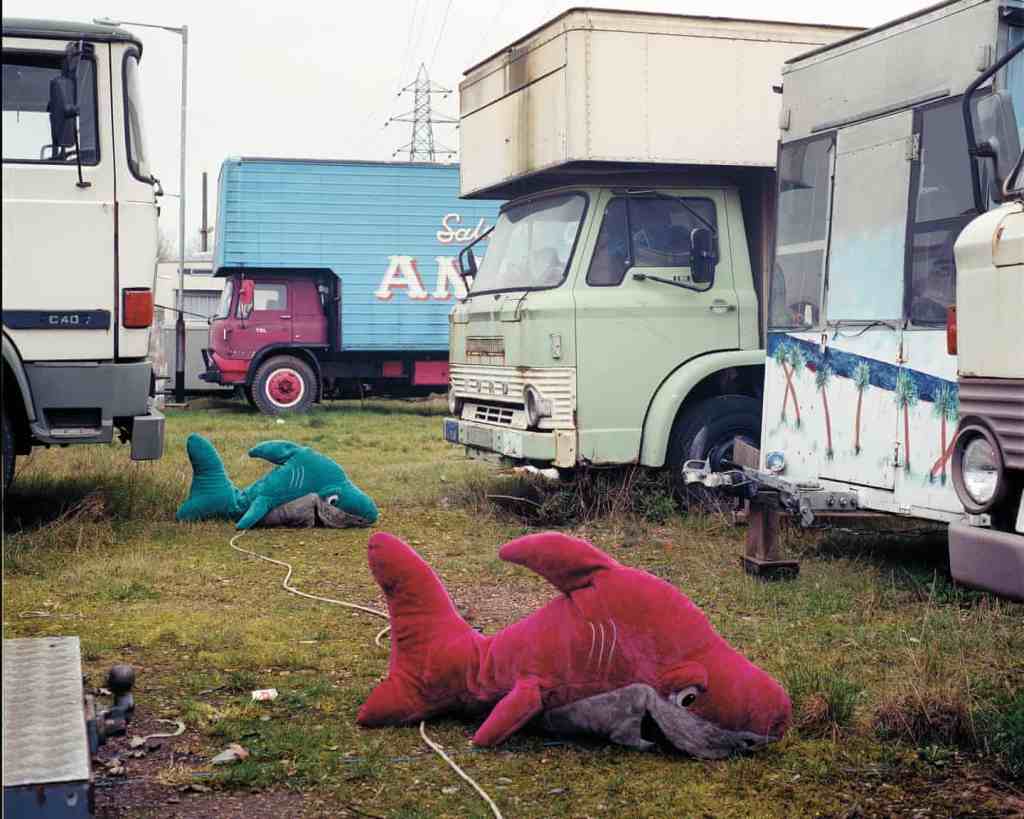

There is an embrace of the happenstance and the accidental in gleaning. When one gleans, it is impossible to predict exactly what one will encounter; there is a deeper engagement with the environment because one loses agency over what one expects. What matters is not what one sets out for, but rather, what one does with whatever one finds.

Jeff Wall’s description of photographers being either hunters – who know what they want from a photograph and go after it – or farmers – who also know what they want but prepare for it by nurturing the conditions of an image – is a useful and supple analogy (Cotton, 2014). This is no clear binary, and Wall makes clear that he often indulges in a bit of both. Likewise, so do I: I decide I want some shots of the grenade range on the Pebblebed Heaths and I track it down – click. I’ve also found a couple of spots that I return to whenever I can to get the right shot, under different light conditions and to test out angles, such as the military bunkers – click, click, click.

But both hunting and farming presuppose that I know exactly what I’m looking for and while my portfolio includes examples of both, the majority of shots included are things I’ve stumbled across along the way, things that have caught my interest and attention, things I’ve picked up, things discarded that I’ve gleaned. So, to add to rather than contradict Wall’s two methods, it makes sense to include another form of subsistence food-gathering, the gleaner.

If the creative work of the farmer is primarily in the preparation, and the work of the hunter is primarily in the moment, then the work of the gleaner is primarily after the event. In the case of Varda, this happens in the sifting, sequencing and tight editing of a huge amount of collected material. This was exactly my approach in the making of my film (In Search of) Old Sunshine: I amassed bits of writing, my own and those of others, visited a variety of places just to see what they were like, returned regularly to one particular green space, talked to lots of people, and then created a film from what emerged from the material.

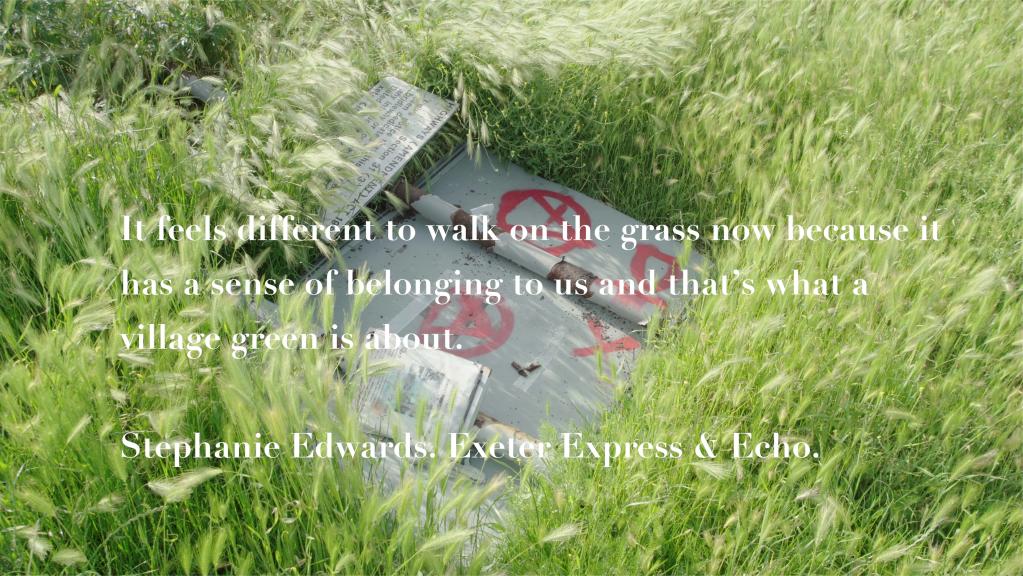

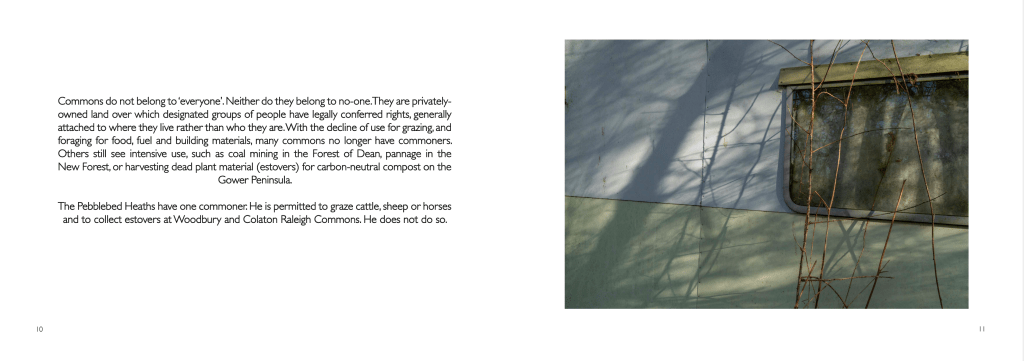

It was also my approach in creating common knowledge, weaving together ‘knowledge’ gleaned from conversations and readings alongside images gleaned from a series of occasionally directionless and impulsive photo walks across the Pebblebed Heaths, and drawing this together with personal observation and speculation. From this, I have drawn together the themes of the portfolio, the subthemes of each double spread, and the main themes – historical context, changing landscapes, working together. The problematic objectivity and vagueness implicit in the title is entirely deliberate, as is the occasionally tenuous connection between text and image. Does the heath’s one commoner really live in a run-down caravan? Is that graffiti really on a military bunker?

There is an important philosophical point to be made here. In the social sciences, such a methodology is known as thematic analysis, and is self-avowedly subjective. There is a general area to be explored, and certain topics to be covered, but the work is essentially a summary of findings rather than a defining argument. This approach is central to the literary essay, and has a companion in the essay film, the loosest of documentary categories of which Varda’s work is considered exemplary. Neither an objective approach to actuality, with its risk of didacticism, nor a wholly subjective one, with its risk of solipsism, an essayistic approach hands agency to the reader or viewer.

But to what extent can photography be considered essayistic? And does the essayistic, being originally a literary form, require text to be considered as such? Aldous Huxley (2017) proposed that the literary essay was a ‘personal investigation’ which revolved around three poles: ‘…the personal and the autobiographical; …the objective, the factual, the concrete-particular; and…the abstract- universal…The most richly satisfying essays are those which make the best…of all three’ (p. 84).

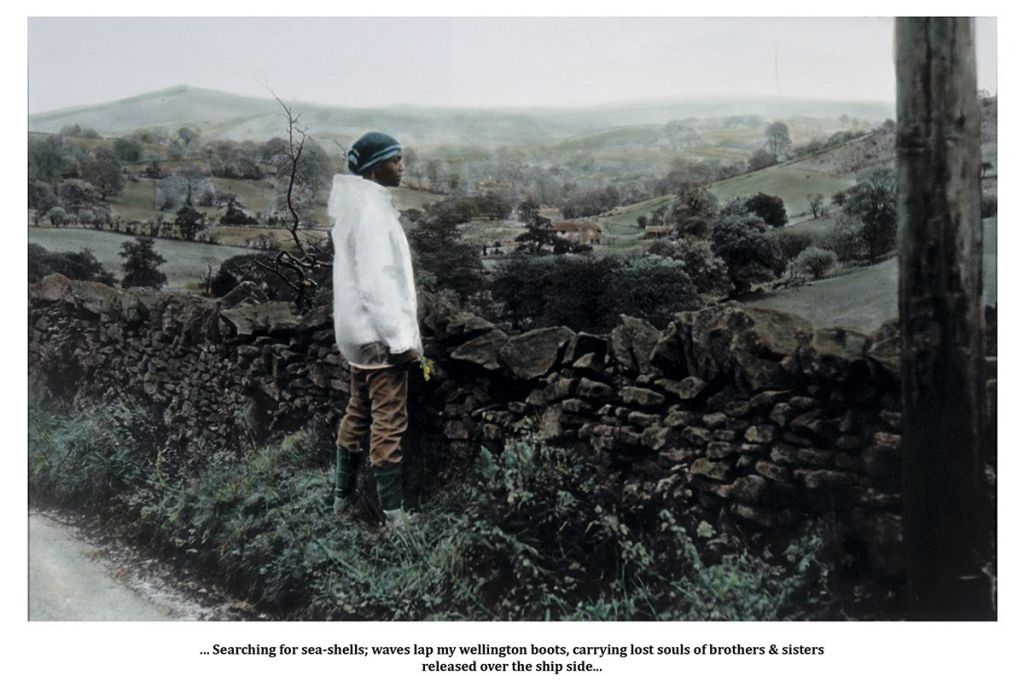

Of this, Ingrid Pollard’s series Pastoral Interlude (1988) is exemplary: the result of meticulous contextual, aesthetic and in-the-field research, deep introspection, and a lively and perceptive philosophising that involves the viewer, uncomfortably so if one is the conventionally white consumer of ‘countryside’ and landscape photography.

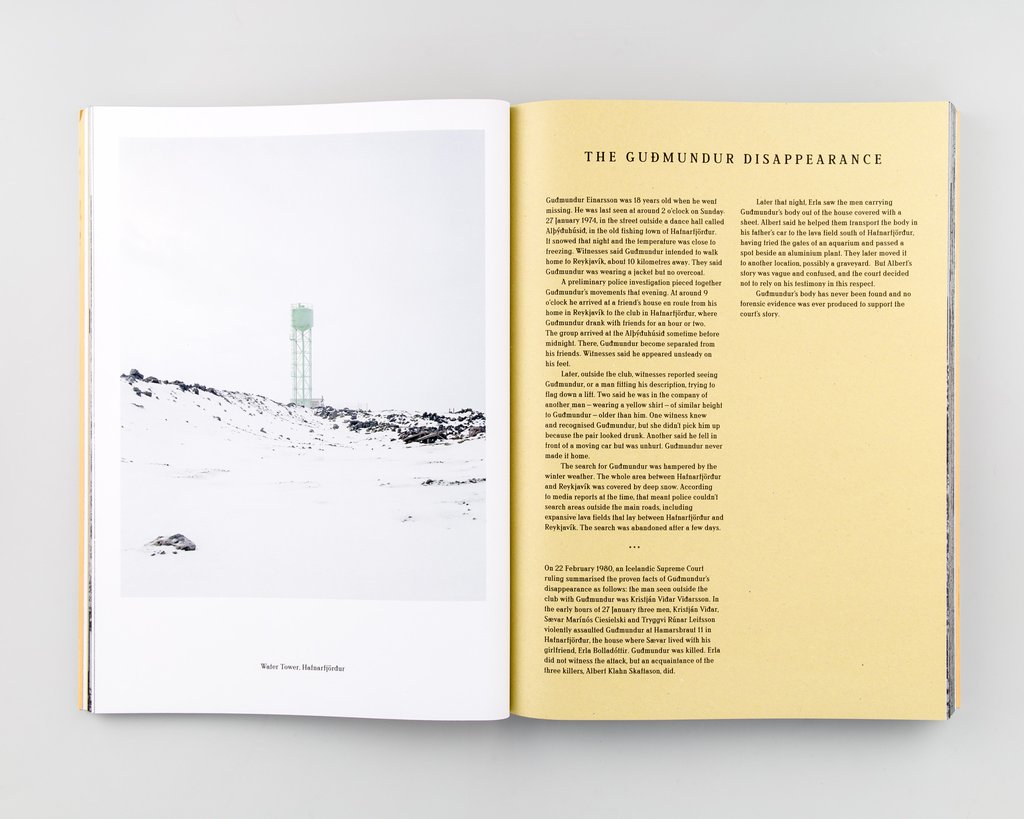

Very differently, Jack Latham’s Sugar Paper Theories (2019) permits the viewer to immerse themselves in the concrete-particular of documents, from which he has drawn out universal themes of identity, authority and the suppression of truth: his personal involvement emerges stylistically, and it is argued that the authoring implied by notable styling works self-reflexively in the essay film to place the filmmaker within it. Here, when placed alongside more vernacular archival photography Latham’s meticulous eye and playful framings imply his presence no less decisively than had his shadow or reflection appeared, and the entire book is, surely, as much the result of gleaning and happenstance as Varda’s documentary work.

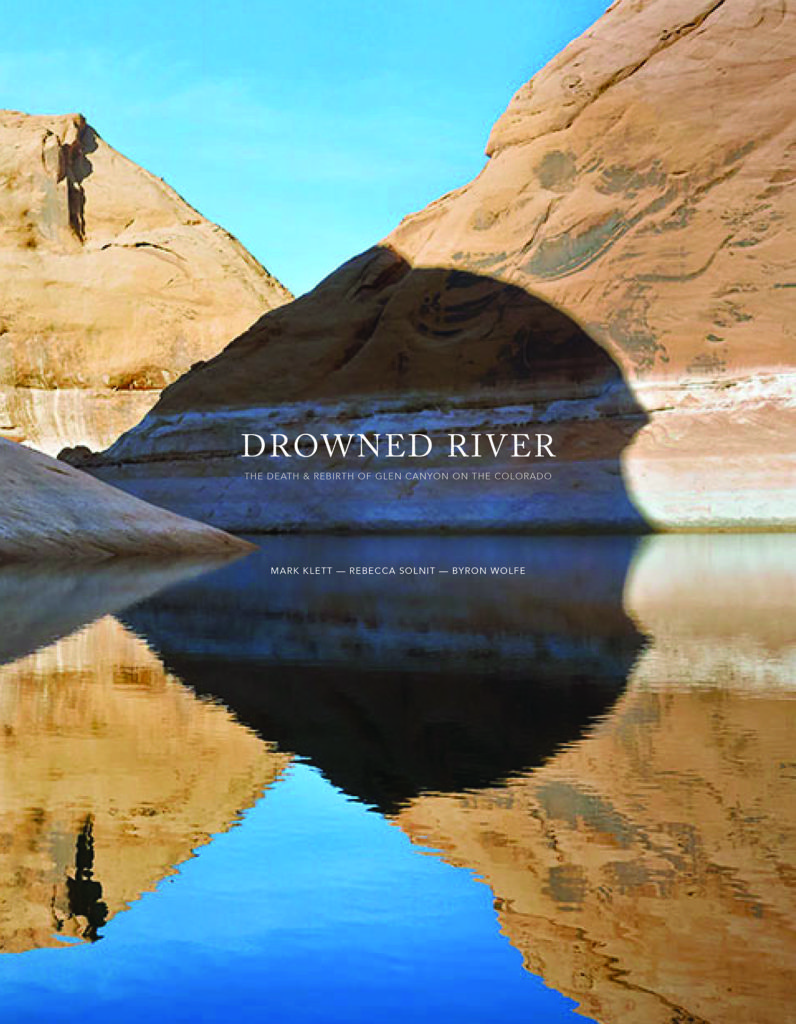

In his essay Truth and Landscape (1996), Robert Adams tells us that ‘landscape pictures can offer us…three verities – geography, autobiography, and metaphor. Geography is, if taken alone, sometimes boring, autobiography is frequently trivial, and metaphor can be dubious’ (14). Here are, extraordinarily, precisely Huxley’s three poles. Having not yet seen Adams’ series, I cannot evaluate this further, but it is intriguing to say the least, especially as Adams’ images are typically presenting without text. As Adams’ work is pointedly but playfully political, and uses aesthetics in complex ways, I intend to do so. My own project is still very much in its infancy. I have much to learn, to explore and to glean. I have barely begun to draw themes or decide on how to address the essayistic in my work. Nevertheless, my work-in-progress portfolio is a very tentative first step towards doing so.

Adams, R. 1996. Beauty in Photography. New York: Aperture.

Andreson, M., & Varda, A. 2001. “The Modest Gesture of the Filmmaker – an Interview with Agnes Varda.” Cineaste, 4. pp 24-7.

Cotton, C. 2014. Photography as Contemporary Art. New York: Thames & Hudson.

Huxley, A. 2017. Preface to The Collected Essays of Aldous Huxley. In N. Alter & T. Corrigan (eds.) Essays on The Essay Film. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 83-85.

Latham, J. 2019. Sugar Paper Theories (second edition). London: Here Press.

You must be logged in to post a comment.