There can surely be nothing further removed from exhibiting in a ‘white cube’ than picking up a dog poo bag from one’s exhibition space before 8am, hoping not to hit the Friday changeover traffic at the M5 junction on the way back home.

I’ve been delighted with how my first exhibition, Hidden Corners, has gone. It was amazing luck that Pebblebed Heaths Conservation Trust’s annual heath week – which coincides with the heather being at its peak – also coincided with Falmouth Flexible’s Landings 2020. Unfortunately, I’ve been too busy with the exhibition, family and work at Devon Wildlife Trust to involve myself much with Landings, which is a shame. But I do feel lucky that I’ve been able to put on a physical exhibition in this very strange year. I also feel really lucky that Kim and Kate at PHCT have been so enthusiastic and helpful.

To recap: a discovery over recent months is that it’s the hidden corners of places that really draw me – places that are a bit overlooked, neglected, a bit sinister, but also full of vitality. They’re places to dream about, prompts for the imagination, and I’ve worked with them in various media time and again. The fascination stems from the books of my childhood and has continued on through my love of horror films. This fascination is not informed by photography, and interestingly, it was brought to my attention as much by my daughter’s imaginative preferences for our choices of family walks.

With my exhibition, I didn’t want to tell people what kind of relationship to have with the images; rather, I wanted them to enter into the process which brought them about. This was in part a result of a conversation with Jesse Alexander early on in the exhibition’s development; he’d mentioned he thought it a bit pointless having pictures of the place where you were already standing, and I agree – doing so would be an arrogant statement that the artist’s vision of a place is implicitly superior to that of the ‘mere’ visitor. I’d been to a photography trail in Fingle Woods on Dartmoor some years ago where huge photos were hung in the trees, and this was exactly how that trail struck me.

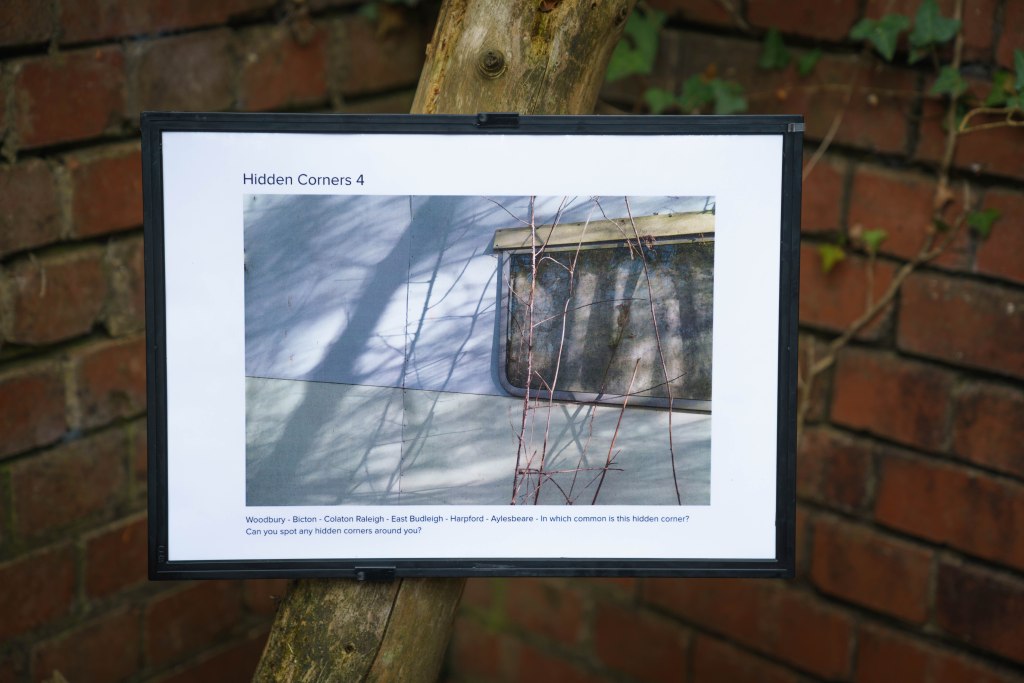

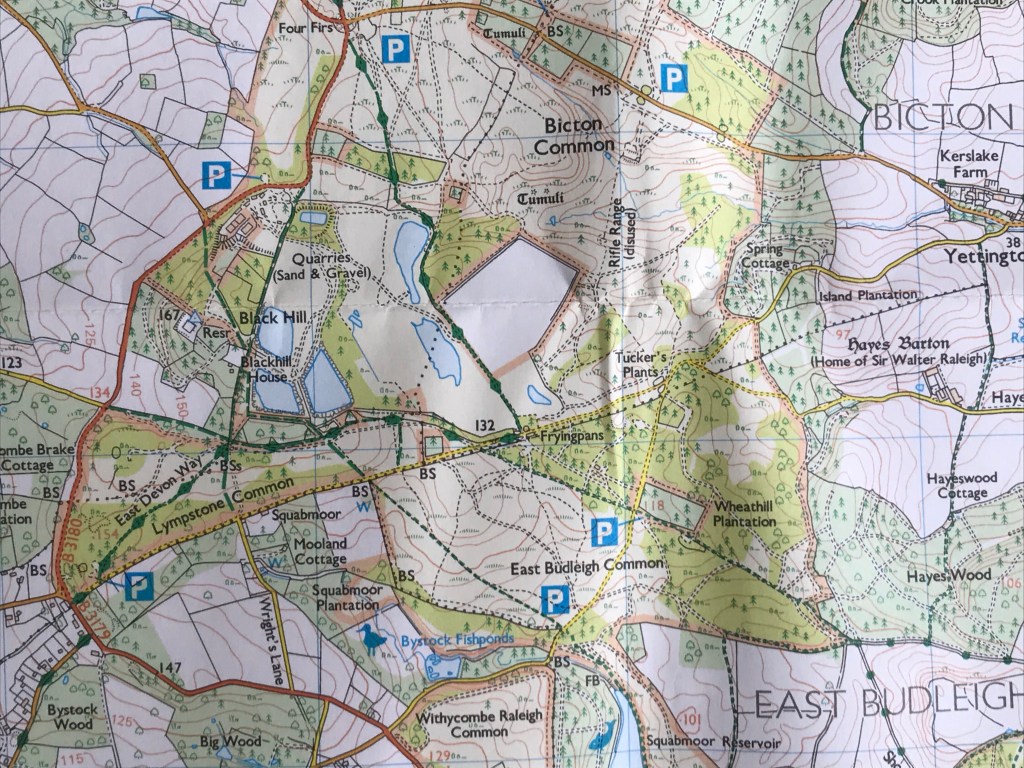

Hence, I came up with a photography trail of around 90 minutes around a lesser-known part of East Budleigh Common, taking in a few hidden corners where six laminated and framed images were planted on wooden stakes. The trail itself and the selection of sites for images are thus an expression of the same thing as the images; they have been selected and arranged in a manner not dissimilar to going on a shoot and editing images afterwards. To this extent, I guess the trail is more an installation than an exhibition. Each image invites viewers to look around for hidden corners close by, and also to guess on which of the six named commons it was taken.

There’s been some good feedback. Everyone, including Kim and Kate, ended up visiting spots they’d never been to before and, as I’d hoped, this proved to be as important to viewers as the images themselves. One respondent is now keen to visit all the spots where the images were taken – which is easier said than done in one or two cases, as it’s quite hard to describe accurately how to do so.

Having walked the trails numerous times, it became obvious that once the exhibition had entered the landscape, it took on a life of its own. First, it was clear that the images were also being encountered individually where they intersect with the habitual circuits of dog-walkers, horse-riders and young families. Doubtless, some would think it just some arty nonsense not worth bothering with, but I hope that most would be pleased to find something a bit unexpected and hopefully like the image, possibly giving them pause to think throughout the rest of their walk or ride.

Second, someone somehow got wind of the trail and put up their own numbered photo trail which in places intersects with mine. The photos are military, mainly tanks, and generally depicting desert warfare. Kim suspects she knows who this might be – a member of the public who has previously taken it upon themselves to inform others about the military use of the commons.

Third, the trail took its place amongst the events of the common. The Royal Marines have been training in exactly this corner or the commons throughout the exhibition, and this has meant that one image, close by a spot favoured for boozy campfires by local teens, has remained pristine and spotless, a series of makeshift shelters being made and remade nearby. Meanwhile another image, housed in a former military hut, was the favoured dumping ground for a particular dog walker’s filled dog-poo bags, and the same place was used to dump Costa Coffee cups (presumably the same person). This has continued throughout the exhibition.

Last, it has entangled me even deeper with the landscape than my photography ever could. Walking between my images early in the morning, blank gunfire all around me as I stride out with my litter picker, has been a slightly humbling experience. However much I might intellectualise my work – and goodness knows, I love to do this – the fact remains that it is grounded fundamentally in the materiality of existence, and is intended to communicate precisely this, even when inflected with affect. It also acknowledges the profound democracies at play on a registered common, that no single experience is more or less valid than the other, and it is for this reason I was quite delighted to come across a rival trail.

You must be logged in to post a comment.