I’ve a lifelong love of horror, ghost stories, sci-fi and fantasy, and though I’ve long been familiar with Freud’s notion of the unheimlich – weakly translated into English as the Uncanny – it’s never sat well with the work I prefer or the moods I sometimes seek out when photographing the landscape. Mark Fisher (2016) has done an excellent job of teasing apart three interrelated but distinct concepts – the uncanny, the weird, and the eerie – and this has helped provide a focus for my work over the past weeks as I’ve roamed in the weird and eerie moods and sensory encounters made possible by the long dusks as we approach the summer solstice.

Fisher argues that while all three are similar in their affect and in their defamiliarising effects, the uncanny is quite different to the other two, pointing to Freud’s original word, the unheimlich, as rooted in the domestic as the literal translation – the unhomely – suggests. The unheimlich, he argues, starts with the familiar and makes it strange from within whereas the weird and the eerie impose strangeness from the outside. Hence, for example, the automaton of Hoffman’s The Sandman, mentioned by Freud, is created out of ideas of the family. The unheimlich therefore requires a degree of retention of the homely to exert its unhomely effect.

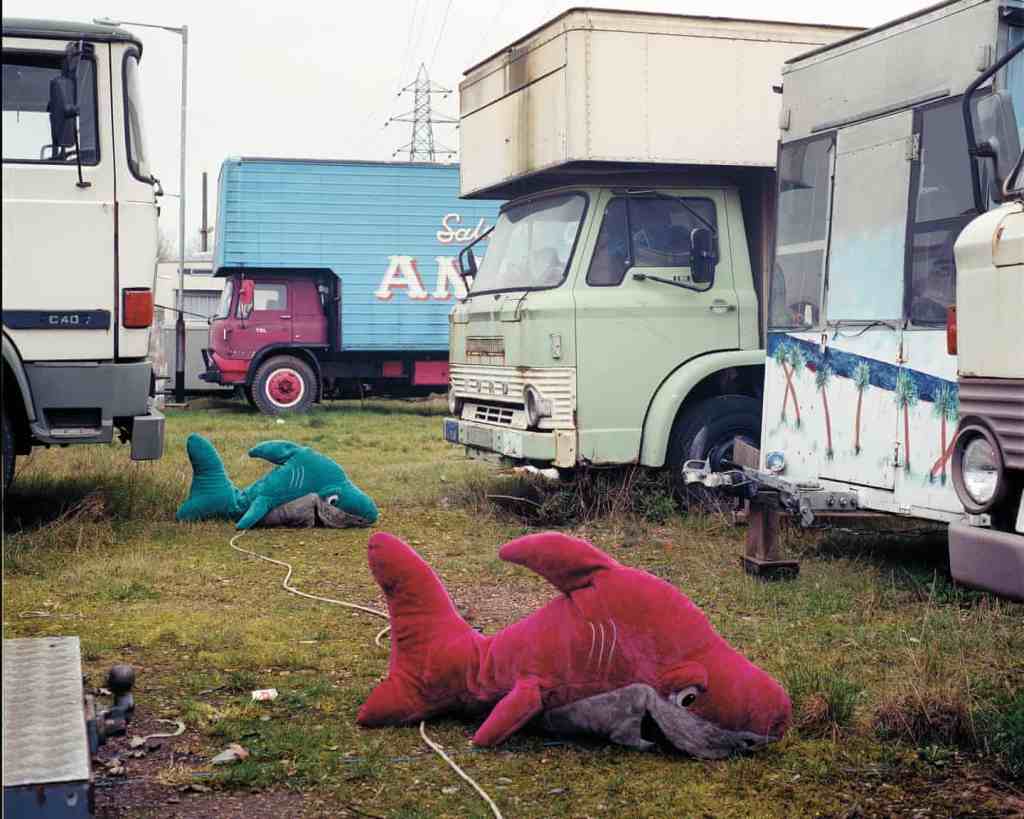

Wyndham’s The Midwich Cuckoos, on the other hand, might similarly seem to be a tale of parenting turned monstrous, but there is nothing homely about its golden-eyed children from the outset; they are imposed from the outside. This is a good example of what Fisher describes as the weird as bringing ‘to the familiar something which ordinarily lies beyond it and which cannot be reconciled with the ‘homely” (10), particularly when two things are brought together that should not logically be, in this case a hyper-intelligent hive mind and biologically human children.

Of course it could be argued that, in the case of The Sandman, the wild science which makes possible the automaton is ‘beyond’ the homely, but I would counter this is only in a very limited way: it is the father’s job, keeping him within the orthodoxies of family structure, and it is also within the orthodoxies of contemporary culture through science, though only just. There is, to the weird, a contingent unknowability, and I might draw the distinction between two canonical doubles, the double often considered as de facto uncanny. The Mr. Hyde of The Strange case of Dr. Jekyl & Mr. Hyde is, like the automaton, a creation of the laboratory. He is monstrous, the science is extreme, but Mr. Hyde retains some of the familiar behaviours and traits of a gentleman; it is this latter that especially provides its deeply unsettling uncanny effects. There is nothing unknowable about Mr. Hyde’s existence – Stevenson saves his explorations of that for his psychological insights. The Portrait of Dorian Gray, on the other hand, is the result of a form of curse which (at least in the book) is never adequately explained. There is a clear intervention of something unknowable from the outside: how has this happened – and why? We are not told. The monstrous double in the painting is thus not homely at all and so cannot be considered unhomely: it is, rather, weird.

Fisher’s idea of the eerie is related but quite distinct: whereas with the weird, something exists where there should be nothing, or where nothing exists where there should be something. Hence, despite its iconic familiarity, the Tardis always retains a sense of the eerie wherever it crops up and hence the empty motorways at the height of lockdown were frequently referred to as eerie. In both cases, as with the weird, unknowability plays its part, though quite differently. The unknowability of the Tardis is the logic-defying otherness of time travel and its Doctor; this unknowability allows the Tardis to occupy tellingly liminal spaces in each storyline, spaces where there should typically be nothing. The empty motorways of March and April 2020, however, did have a logical, knowable cause – the application of government restrictions in response to a global pandemic. All the same, empty motorways are not a unique phenomenon and can be caused by serious accidents, road works, demonstrations, and do not then appear eerie. I would argue that a failure to fully accept, grasp and adapt to a reality that was continually shifting and unpredictable was behind this feeling of eerie more than any connection with apocalyptic cinema. One simply did not know when, if ever, the motorways would run again, and this demonstrates how an unknowable outside acts on the familiar to render it eerie.

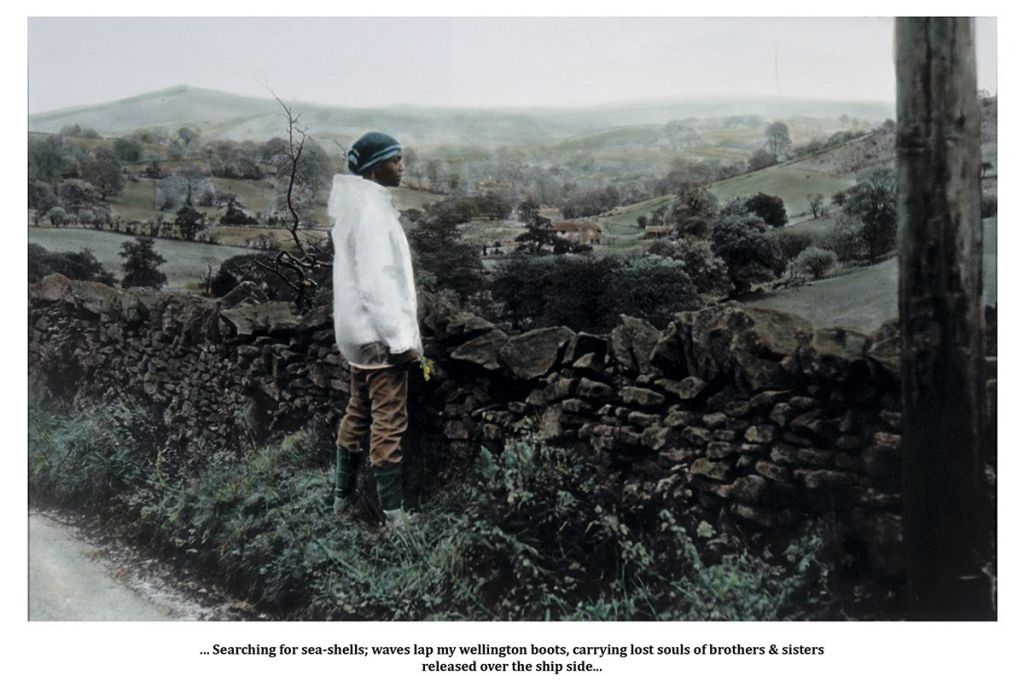

So what has all this to do with my practice? First, one has to acknowledge the utter subjectivity to applying these modes. One has to experience a familiarity in something to experience the uncanny; one has to experience a lack of knowledge of what should or should not be to experience the weird and the eerie. The failing light of dusk helps to weaken certainty just as the purple hues accentuate strangeness. In such a state of mild reverie, it becomes easier to suspend what might otherwise be knowable and suggest less literal readings of the landscape.

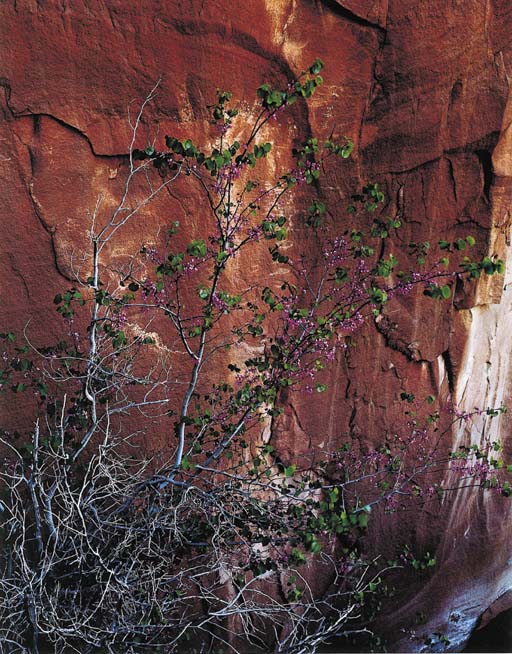

Hence, the fallen and felled trees entangling roots and pebbles seem to become a single, Lovecraftian organic entity; what has caused this fusion of vegetal and mineral is unknowable; it becomes weird.

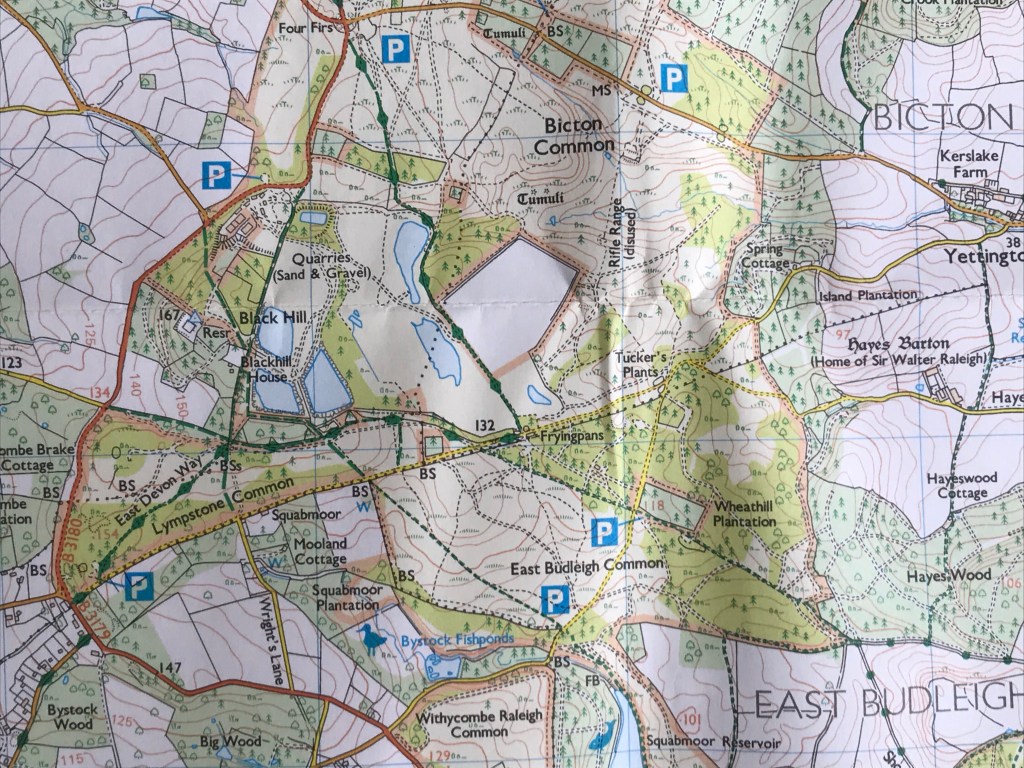

Hence the child’s drawing which does not belong in the brambles of East Budleigh common sheds daylight’s familiar explanation of a family picnic and infers a family snatched by fanged monsters.

A chunk of the Rock of Gibraltar sits on a rise on Woodbury Common, a commemorative gift for the Royal Marines who first cut their teeth there. The rock is a pale blue and always looks out of place, but the dusk makes it shine purple against the dark heathland vegetation and its shape becomes a ghostly abstract. In the midst of this darkening landscape where there should be nothing, there is a palpable eerie something; perhaps the rock fulfils a darker purpose, perhaps some obscene evil lurks beneath it.

In the daytime, these army tracks lead to one of the flagpoles used to warn the public of the firing of live ammunition, but after sundown, the tracks and empty flagpole imply the absence of human activity, indeed the empty expansiveness of the heaths. Where has everyone gone? Will they ever return? It is easy to fall into such reveries without altering or fictionalising anything in front of the camera.

Commons are complex places, full of lost histories, silent wars of attrition and endless idiosyncrasies. Beyond being a place for picnics, dog-walking, den-building and mountain-biking, they are places of conflict and violent change, both political and environmental. The pebbles themselves are evidence of millions of years of violent climate change during the Triassic age, a long way from the comfortable beach pebbles one puts in one’s pocket. I have been searching for a way to incorporate this with the familiar and comforting way the heaths occur to most people. It may be that through deploying the weird and the eerie, sparingly perhaps, I might be able to achieve this reconciliation.

Fisher, M. 2016. The Weird and the Eerie. London: Repeater Books.

You must be logged in to post a comment.