As coursework for my Masters in Photography, this is a presentation on my current practice and my Hidden Corners project.

Category: PHO701: Critical Research Journal

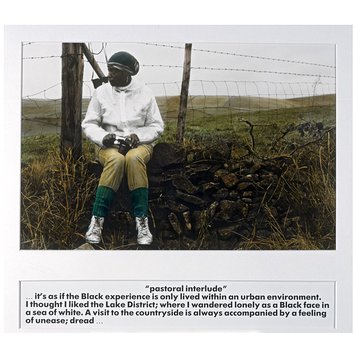

Picture of the day – Ingrid Pollard

I got talking to an art historian last night who specialises in black women artists of the 1980’s. The historian knows Pollard very well, and it’s a name I’ve come across a few times and meant to check out – as her landscape photography is highly political and very subjective. This is from her book Pastoral interlude, from 1988.

The photo has an extraordinary depth and a great many layers of meaning. The photographic process – hand tinting – takes the viewer first back to the nostalgia of hand tinted postcards, but then, when weighed against the subject of a black woman, one encounters the prejudices and exploitation of the British Empire. Nostalgia is challenged just as the present, with its prejudices and exploitations, is contextualised by an ever-present past.

Pollard’s pose likewise unsettles. Sitting on a dry stone wall, knees bent inwards, her posture, and her clothes, are identical to any female rambler. However, her very dark skin contrasts with the white coat, her headscarf bulges as if hiding dreadlocks, and again the familiar is unsettled, something that is echoed in the text: we feel Pollard’s unease.

As elsewhere in the book, Pollard is excluded from the landscape – here explicitly by the wall and the barbed wire, but also implicitly, hemmed in by the framing fence posts. In fact, the vista occupies only a fraction of the photo, and appears flat, an almost abstract stripe of largely uniform texture.

But Pollard is victorious. The camera in her lap is an expression of agency and power. Her partial profile accentuates her strong facial features and, like the camera, the force of her gaze – though both are directed far away from the recording lens. Moreover, Pollard’s skin tone is precisely echoed in the dry stone wall, perhaps the most archetypal symbol of the Lake District. While Pollard remains separate from the landscape, she is one with the power structures which define it.

A picture a day – John Gossage

John Gossage has been one of my big discoveries during this course, recommended by one of the staff at the Martin Parr Foundation. His book The Pond appealed to me initially as it’s an intensive, evocative examination of a place that includes many elements also of interest to me – borders, misuse, traces. But what Gossage has really opened my eyes to is the possibility of texture – and specifically messiness, scruffiness.

I’ve long been drawn to line over texture – as in my motorway bridges work, tree shadows, pylons, field patterns, and of course urban environments. But nature is messy, and that mess thwarts clean lines. Gossage embraces that mess – to an extent, so does Baltz – and yet elegant use of line emerges in a symbiotic relationship. This picture is an excellent example. The right third of the frame is a mess of leaves, and the left hand river bank, which would have given the right hand back’s curve emphasis, is hidden behind a small, scruffy tree. This undermines what could have been a picturesque river curve, but it also echoes the scruffy path running alongside it. The Pond demonstrates an unofficial, uncurated natural environment, its human paths more like animal tracks, as if somehow such an environment, with its litter and forgotten barbed wire, is closer to ‘nature’ than the carefully framed and composed places of more conventional landscape photography. Such unfussy human intrusion is present here in the sawn-off branch, an act of violence perhaps, that acts as counterpoint and subversion of the upright trees to the right of the photo and the very young tree in the foreground, the image’s only clean lines.

I’ve embraced mess and found form in texture since encountering Gossage. It’s been a revelation, and has also helped me rethink colour. As my commons project will include the messy landscapes of heath and birch woodland, this is just as well.

Tunbridge Wells Common

A trip to my home town, which has a wooded common at its heart. The flat light was wonderful for bringing up the textures and colours. I’d anticipated exploring both Tunbridge Wells and Rusthall Commons, but only managed half of Tunbridge Wells’ – there was far more to find than I ever imagined.

Thoughts on Style and Content at Woodbury Common

Wandering around Woodbury Common and enjoying the murky flat light, something I’m embracing I think in response to this course, perhaps because it’s stepping away from the picturesque. Many thoughts. First, that the M5 bridge project, though something I love, is fundamentally shallow, ornamental, pretty. That’s not to downplay it, I’m proud of some really great images, but if I want to say more, use photography to analyse deeper, I’m going to need something more complex. It’s been really useful as learning exercise, and it’s not finished, but this is very much a personal project, its final form impossible to predict, though I suspect when I have the images and guts to do so, it’ll be a collection of abstracts.

Second, that I need to migrate my feelings about filmmaking to photography – that is, rather than a painstaking wish to get the best shots, then and there, think ahead, take time, my restless, ranging approach is just fine. It’s gleaning. Collecting. And, like Varda, it comes to make sense not in the decisive moment, but when put in combination. I need to think not in terms of single stand-out images – which I have hitherto – but of images that form part of a whole, maybe that rely on one another to persuade and express.

Third, that I won’t be able to express everything I need through photography, just like I needed my voiceover for my filmmaking. So, rather than seek photographs to stand in for information, or write to describe photographs better, I should let photographs express what they express better than words, and words express what they express better than photographs. How they fit together, who knows. It’s early days.

Fourth, that I’ve chosen something more complex and ambitious than anything else, including film. There’s a need to adapt my style to my subject – to look out for ways of using my lines (like in tracks) and my colours (like in light) and the strange (like the leylandii) and the political. I should look at how a photographer with a recognisable style transfers between very different subject. I should go back to Shore’s Survivors of Ukraine(2015) and go in deep there, but be alert for more – like Davies’ European eyes on Japan (2008).

Fifth, that if I’m going to go for a time of day to be photographing, then it’s got to be dusk.

I think that’s some quite good thinking to be going on with.

Markerink et al. 2008. European Eyes on Japan. Tokyo: EU-Japan Fest Japan Committee

Shore, S. 2015. Survivors of Ukraine. London: Phaidon Press.

David MacDougall: Meaning and being

It’s wonderful when coming across a piece of writing that’s so timely, you want to grab the person nearest you and go – listen to this, no, really, LISTEN. Fortunately, I’m not given to doing this.

Such a piece of writing is David MacDougall’s Introduction to his collection Film, Ethnography and the Senses (2006), subtitled Meaning and Being. I’ve come across MacDougall in the context of documentary and for some reason it didn’t chime with me. I suspect, had I come across it again while making Strands, I would have had a similar response. MacDougall is an ethnographic filmmaker deeply embedded in questions of agency for the ethnographic subject, the role of filmmaker, and the distinctive function of film as a form of ethnographic research. In his introduction, MacDougall largely speaks of filmmaking, but speaks for the most part about the function of a camera in producing knowledge, and in this he often equates filmmaking with photography, while noting their very different qualities, especially with regards to time.

I’ve highlighted nearly the entire introduction, so summarising it and responding to it all is more than I’m prepared to do here as yet. What MacDougall explores so thoroughly is that knowledge is constituted not just by interpretative, categorical and analytical meaning, but by being, the immediacy of experience which is provided by the senses. He argues that academic study eschews the latter, despite its putative function of aggregating and developing knowledge. The camera is powerfully placed to provide both kinds of knowledge – even in photographs or films which are deeply analytical, such as those of Wall, a trace of being is retained such that meaning is always provisional and incomplete. Meaning, however self-consciously or unselfconsciously, can be created by framing, mise en scene, instance, colour and so on, but the camera always captures a surplus to any meaning, including the trace of the camera and the photographer or filmmaker’s being in the world (I’m assuming MacDougall is referring obliquely to Heidegger here). This surplus, he argues, is not incidental or accidental, but communicates a surplus of experience, the act of looking as well as what has been seen and utilised to create meaning. This tension between the two forms of knowledge is a strength for both media, as it is creative productive.

MacDougall goes on to argue that while disciplines such as anthropology make use of being-knowledge, they incorporate it into meaning-knowledge in the form of essays, papers and books, at a higher level of abstraction. They do not use it as a tool or form of expression. His understanding of looking is neither passive seeing nor concerted seeking, but aware and open observation, a form of thinking.

This is EXACTLY what I had been engaging with during the making of my last two films – using the lens as a form of analysis and engagement, informed by research but not enacting it as such, not looking for proof or evidence but what Rascaroli (2017) calls a ‘thinking-through’ found in the essay film. It’s really interesting that MacDougall equates film with photography, as that’s what I’d come to understand too, and it was important for me to leave that surplus in. It’s a specific kind of looking.

How this equates to sensory ethnography is something I’ll have to return to, but I look forward to reading this book further.

MacDougall, D. 2006. Film, Ethnography, and the senses. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rascaroli, L. 2017. How The Essay Film Thinks. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

A walk in East Devon

I’d scheduled a visit to Greenham Common today, but my brain decided last night was a great opportunity to wake up at 1, fret, and then think over coursework. Cheers, brain. So a 6 hour round trip wasn’t on the cards and instead I headed up to the Pebblebed Heathlands, a 40 minute round trip. Actually, maybe brain wasn’t being such a numpty after all, as the ensuing train of thought was productive and clear.

The first thing today made totally clear is just how impractical my intended project is. Sure, it’s a great project, but the amount of travel it’d involve will cost money I don’t have and cause disruption to home life if I’m doing it properly. Fact is, it doesn’t have to be done like this. I can investigate commons without needing to visit them all. The Pebblebed Heathlands are fascinating, known to me, and there’s even academic research that I’ve used previously, love, and can go into more deeply. If I’m developing a project about connectedness to land, and if I’m taking a phenomenological approach, then I need to develop my own connectedness to a common, which I can’t do if I’m flying around the country. I’ve been weighing up whether the project should be many commons in no great depth, or one or a couple in depth. Given my inclinations and limitations, it makes sense to go with the latter, and it will also give me the chance to develop a knowledge of sensory ethnography, use money for equipment, and develop a project more connected to Strands and to the possible future PhD with Gideon Koppel. So, OK brain, you win. You were right.

It’s also worth thinking more about the place of research into commons and photography. There’s no reason they can’t be separate but connected. I can write a series of essays on commons generally. I can investigate commons in East Devon through photography. Each can stand on its own, and I like the idea that the photography shouldn’t need explaining. But the two can be connected by approaching the same subject in different ways. Also, why can’t the photo project be like a diary? Entries date, weather, time – rather than trying to get all the shots alike. Food for thought.

The Picturesque and the Sublime

These two words come up again and again and again in my reading and in discussions with tutors. They’re not unfamiliar – I’ve read Austen’s brilliant parody of picturesque in Northanger Abbey, I’m attuned to the Victorian quest for the sublime in places like Tavy Cleave on Dartmoor, I know enough about Capability Brown gardens to appreciate their picturesque, and of course I know the contemporary meanings – very different in the case of sublime. But as terms I’ve never come across their mention in such profusion as in photography. Perhaps that’s due to their powerful connection to ways of looking, something even more relevant to photography to film, and with their roots in painting, to which photography is more connected as a discipline than is film.

It’s proving useful as a way of understanding my own photography. I now realise that I largely avoid the picturesque – or if I do so, it’s with the intention of sharing an image with people who I know will draw pleasure from it, like my parents. But my relationship to the sublime, which I now see I have fully imbibed through landscape photography, is much more complex. I like bleak moorland shots. I like dramatic post-industrial shots. I like wild skies and rugged coasts. Beginning to understand the sublime is helping me unpick why I often find the shots I take of these unsatisfactory: like the picturesque, they’re driven by emotional response, it’s just I came to find a response to the sublime more satisfactory than the picturesque, somewhat noble, even a touch pompous.

Of course, there’s nothing whatsoever wrong with taking pictures just for their emotional charge, or sharing them. It’s just that, with the kind of analytic mind I have, I always want to go deeper, communicate more. A sublime shot becomes apolitical – even where the subject matter is political. And following the thinking-through style of filmmaking into my photography, analysing and communicating through a lens should be paramount. This can be brought about through subversion – it’s easy to subvert the picturesque, which lends itself brilliantly to parody, but how to do the same to the sublime? One strategy I do use is to bring the two together in a single shot – pretty flowers against a mass of concrete. But there must be other ways. And I must think more about suggesting political context somehow. Just thoughts for now.

Phototherapy

I’m drawn to certain places to take photos. I’ll visit them. There are also places I avoid, or don’t bother to bring a camera. I don’t really like Exeter, though I do like the outskirts – and of course there’s the bridge. I do love Bristol, and the grubbier the better – yesterday’s river walk was heaven. And while I’ll walk in lush woodland or magnificent coastal scenery, I’m not really there for the photos – though obviously these do happen. When I’m out specifically to take pictures, and also when I’ve decided not to bother, it’s worth thinking about.

I think I’m looking for something, or looking for a means of expressing something, or of thinking something through. The places I choose are often damaged, but they’re also beautiful, and it’s that clash of such things I seek. They’re places where melancholy, desperation and joy coexist. They’re contradictory but I can make them complete through photographing them, chaotic but I can find order through photographing them. I can’t think of anything more fundamentally therapeutic than that. When I photograph, I’m externalising the mess of thoughts and emotions inside me. I’m making sense of them, finding equilibrium, embracing all of it, and finding beau

Martin Parr Foundation visit

I love going to the Martin Parr Foundation even more now I’ve found the river walk to get there, with all its industrial sites, graffiti, bridges and trees. The Japanese knotweed is particularly splendid this autumn.

I looked out several books I’d wanted to find based on recommendations and Jesse Alexander’s Perspecitves on Place (2015). First up was Mark Power’s Superstructure (2000), which documents the construction of the Millennium Dome, now the O2 Arena.

I’m undecided about Mark Power, as sometimes he comes across like a more showy Stephen Shore, but some of his stuff I love. This is a magnificent book, not simply because it takes you into the heart of something you wouldn’t have seen otherwise – the early stages of construction are epic. I loved his sense of the absurd – workers in the newly openned McDonalds’, the off limits human body exhibit – but more how he intersperses the epic with the micro details of the work – racks of mugs, wood shavings.

It’s strange having few people throughout, in what must have been a very busy site. It makes it seem oddly quiet, which it wouldn’t have been, and that adds to the epic, cathedral feel of the images. Activity is filled in with the details, and where workers appear, they also seem like details – blurred, backs towards the camera, just their feet overhead. Not focussing on people keeps the attention on the structure, rather than the human stories involved in its making. The time scale is that of the building, with occasional contextualising historic details like brand names, papers and TV shows. Time is moving on, though – the ruins and rubbish of the area at the start, the trees lines up and awaiting planting. Only 1 image exists after the openning, distant, blurred, almost as if the whole thing was pointless and the construction was the main event. Given the problems of the dome in the following years, that assumption is accurate.

I looked through several of Jem Southam’s books. Red River (1989) is a river that flows in West Cornwall, and it’s scenery I know, like much of Southam’s. Very well, in the case of his Exe Valley work. Red River, created with poet DM Thomas, doesn’t aim for smoothness, and he draws on numerous styles, abstracts, animal shots, puns. Like Power, he shows community and place largely without portraits. The portraits do seem like interruptions, like speech in a speechless film. I like his contrasts – garden flowers and grotty farmyards and John Davies-ish industrial shots. I liked Rockfalls, Rivermouths and Ponds (1999) much better.

I can see what I’d been told about with typologies here – putting them together connects and creates a distinct effect. I wonder if the typologies of commons should be together, rather than the specific commons. There’s something particularly Becherish about the rivermouths and ponds. Southam seems largely to work in the early morning, before breakfast, again something I’d been told about and worth bearing in mind. Time is also really important – changing tides, seasons, and the cliff erosion – what Southam quotes as “creep” events – events on a really, really slow time scale. I should think about time in my project.

Isaac recommended I look at John Gossage’s The Pond (1985). This is great. He said you’re not really sure if it’s the same place or not in the book, but it feels as if it should be. Gossage has a fascination with paths, traces and borders as do I.

The landscape here is vague, unspecial, it’s an unofficial countryside, to quote Mabey (2010), and the aim is like an exploration and an evocation rather than a document.

The photography isn’t technically accomplished. It’s not smooth. But that fits the subject and there are fascinating effects used with depth of field, something I should consider. There’s a real sense of looking around, at the ground, through trees, overhead. He does some similar stuff with There & the Gone (1997), but that feels more strained.

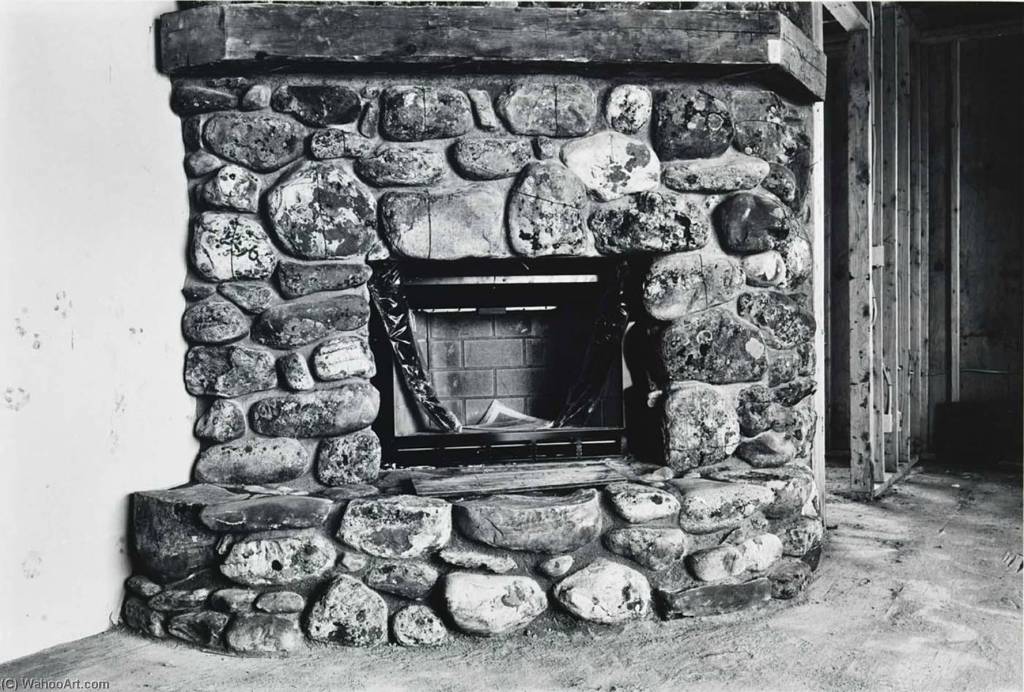

Isaac also recommended I look at Baltz. Park City (1981)is like a scruffy John Adams, much less beautiful and poised. More texture than line. Again, like Powers, busy building sites with absent activity. I loved Baltz’ use of typologies – waste heaps, unwired sockets, fireplaces, wood shavings.

There’s a sense of time moving with dust and fire, but also stillness. It’s unnerving, though less so than San Quentin Point (1986) which looks at litter as if it were found on the surface of the moon. I found this impenetrable and boring after a while, though I appreciate its defamiliarising effects which make the litter look genuinely horrifying rather than simply morally wrong.

Borderlines (2008) is a book of interviews about The Troubles with people living at the Irish border – particularly poignant, upsettingly so, given current events.

The book was created in the wake of the Good Friday Agreement and both sides saw joint EU membership as a means to peace. Sad. The photos aren’t all great, but there’s a casual focus on the banality and casualness of horror – murders at crossroads, a dead fox on a fence, a caged CCTV camera, as if the photos contain hidden codes and latent violence. It was hard to see how they fitted with the interviews, though.

Gilligan’s DIY/ Underground Skateparks (2014) depicts skateparks around the world, and while there’s an interest in seeing the variety and sameness of them all, the interest wanes fast – the portraits are horribly contrived – and it felt like he needed to work harder somehow. The shots are too dissimilar – especially a few stunning ones in Germany – and a sudden leap to golden hour footage seemed amateurish.

Paul Hill’s White Peak Dark Peak (1990) is a stunner. He’s fascinated with lines in the landscape, especially faint ones like badger tracks, and something that only works well in black and white, as I’ve found for myself. He has an eye for the surreal and macabre – the wallaby in vignetter, a rotting badger through the year – and typologies – mushroom circles, tussocks, dead trees.

Shots are repeated almost identically, some as places, but others as positioning for flowers, for example. Oddly, the exactness and repetition between seasons makes the landscape seem unchanging.

Alexander, J. A. P. 2015. Perspectives on Place: Theory and Practice in Landscape Photography. London: Bloomsbury.

Baltz, L. 1981. Park City. NYC: Aperture.

Baltz, L. 1986. San Quentin Point. NYC: Aperture.

Brady, T. et al. 2008. Borderlines: Personal Stories and Experiences from the Border Counties of the Island of Ireland. Gallery of Photography. Dublin: Gallery of Photography.

Gilligan, R. 2014. DIY/ Underground Skateparks. NYC: Prestel.

Gossage, J. 1985. The Pond. NYC: Aperture.

Gossage, J. 1997. There & Gone. Munich: Nazraeli Press.

Hill, Paul. 1990. White Peak, Dark Peak. Manchester: Cornerstone Publications.

Mabey, R. 2010. The Unofficial Countryside. Stanbridge, Dorset: Little Toller Books.

Power, Mark. 2000. Superstructure. London: HarperCollins Illustrated.

Southam, J, & Thomas, D. M. 1989. Red River. Manchester: Cornerstone Publications.

Southam, J. 1999. Rockfalls, Rivermouths and Ponds. Brighton: Photoworks.

You must be logged in to post a comment.