It’s been a pretty painful few weeks. First, Jesse pointed out – well, someone had to – that my woodland project was, especially in the current circumstances, perhaps a bit ambitious within the timeframe. It’s a great idea, and something to work away at slowly, but letting go of that as the next hot thing for me was tough, especially in the absence of any coherent idea for this module.

Second, and this might sound ridiculous, but the arrival of the Sony A7siii has thrown me more than I could possibly have anticipated. Not the technical headaches it caused – £399 for a new memory card, £270 for an upgrade to my editing software, and all of this more or less worked out single handed. Nor specifically the anxiety caused by changing camera in the early stages of my first major commission. But the possibilities suddenly opening up. Because unlike my previous Sony, the A7siii shoots video to the same quality as my stills cameras. And this has thrown absolutely everything, finally broken down the wall between my film and photography worlds, and meant that I no longer need to work out if I’m a filmmaker or a photographer, but able to occupy and explore the middle ground.

I looked into the relationship between the moving and still photographic image during my Film Masters at Bristol, but not revisited this research, over two years ago. Likewise, I’ve been curious as to why it’s OK to work in video on a photography MA, and how video operates differently in this context – as it must for the sake of disciplinary coherence. And given that I’m hellbent on doing a film PhD with a supervisor from a fine art background, it makes sense to spend the coming module reconnecting with film in a fresh context.

So I’ve ordered a bunch of books, got a few recommendations, revisited some practitioners who work in both, begun asking around for recommendations and advice, and one of the things that occurs to me is how comfortable I feel occupying this middle ground, how much I’ve already thought this through, perhaps even without realising it, and how it maybe gives me a critical edge with my photography, in a contemporary context where awareness of the medium is so utterly central. This could be my niche.

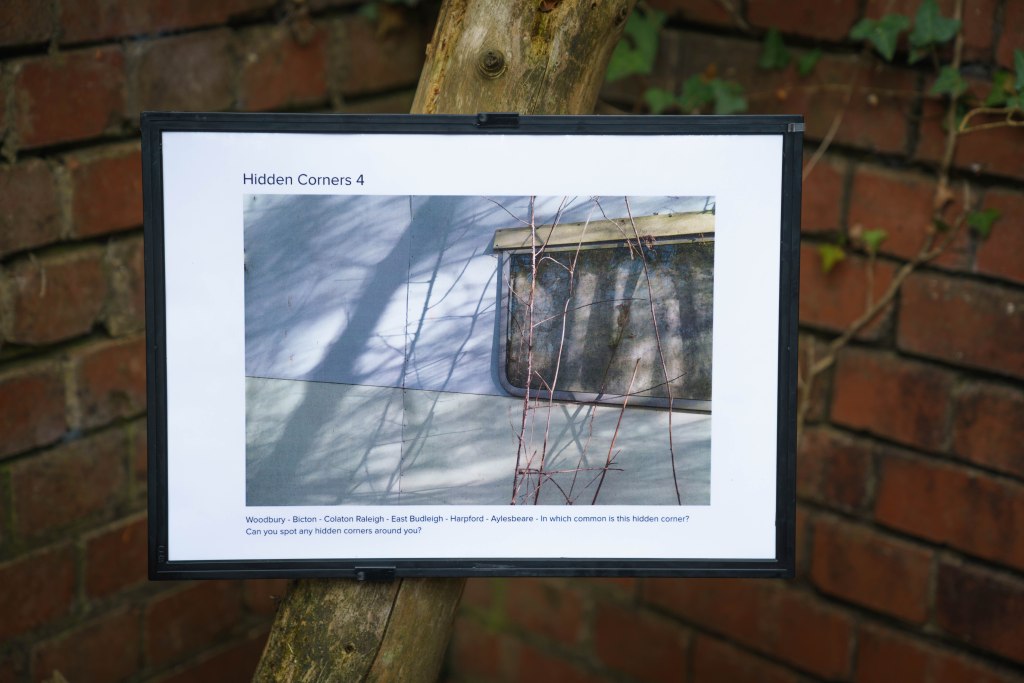

So, today and earlier in the week, I’ve been out at Woodbury Common, tripod over my shoulder, filming. As a filmmaker, I work much more like landscape photographers who use large format and view cameras. Working with a tripod, shooting less, covering less ground, this is how I’ve always worked as a filmmaker. I really go in deep, interrogate details in a way I don’t with stills. And so I thought, if I’m to keep things at the heaths, rather than the great roaming explorations of the past year, I’d pick an idea, or a theme, and explore that. Keeping with commons, I thought enclosures would be good, especially given that the heaths have some odd little enclosed pockets which have their own distinctive sense of place.

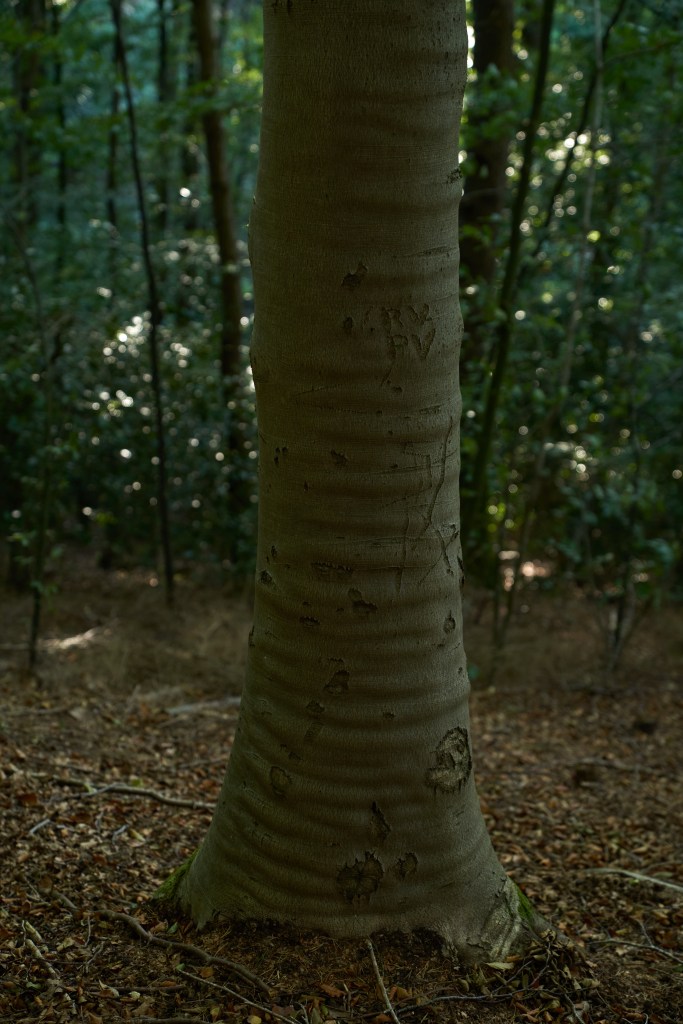

Today, I decided to explore what’s known as Diamond Plantation, a tiny rhomboid woodland on the bank of a valley mire which is surrounded by enclosure embankments. No particular agenda, just seeing what happened. I knew I wanted to express a sense of the place – so views from the rises around it, the sounds and vegetation to be found there. But what I didn’t expect was to come full circle with the Hidden Corners/ childhood idea: these odd little places have become places because they’re enclosed. They’ve become anomalous in the landscape by being enclosed and improved, developing a separate character, and that makes them magic kingdoms, with portals and potential. More, their very enclosure invites invasion, reminding me of breaking into forbidden places, especially gardens, when I was a child. And so I’m able to bring to these profoundly political, violently exploitative places, the imaginative anarchy of childhood. That’s pretty damned cool – and it’s also perfect that there are vestiges of all kinds of games here – dens, a smoke grenade, bike tracks. I found myself drawn to the fantastical – eerie wood shapes, a fly agaric, pitcher plants. My eye for the fantastic is undiminished, it turns out.

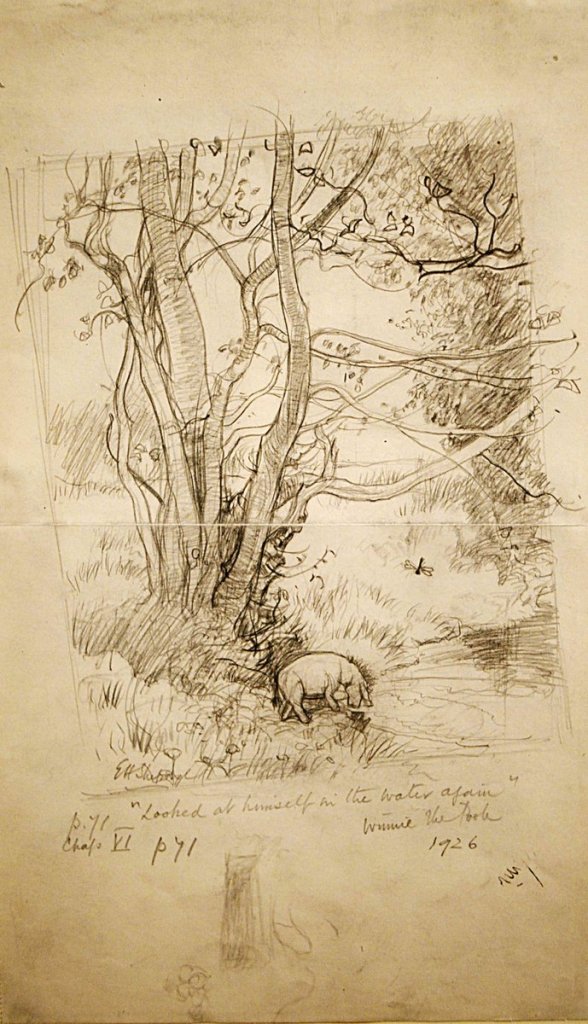

Around these places, I think I can work out everything I need to: deepen my understanding and connection with commons, and these commons in particular; expand on the childhood themes from hidden corners (one or two shots recall, deliberated, E.H. Shepard); give me the opportunity to interrogate the overlaps and divisions between still and motion photography through my own work and research; bring to bear on my filmmaking what I’ve learned about photography over the past year; consider how still and moving image can be combined into one body of work (the stills from this camera are excellent). I also remembered just how abstract light can become in video – watching sun sweep through a valley: you just can’t capture that the same way in stills.

I’m also thinking through the Wellcome Brief – focussing on the devilish figures in the burned gorse and the crucifixes in the dead trees emphasise the fantastical dimension of eco-anxiety. Likewise, keeping these in a very shallow DOF emphasises the narrowness of vision thinking like this entails. I think this will work.

You must be logged in to post a comment.