I like to spend a while mulling things over before writing anything down, so the gap in this CRJ indicates significant mulling. In light of various constraints, discoveries and understandings, I’m now moving the focus of my work on this Masters away from registered commons to woodland. Of course, that’s not to say none of the images I’ll be making will be of registered commons, as significant woodland is often found in such places, but the social, cultural and historic fact of commons now assumes a lesser importance. It’s also worth mentioning – though in itself this merits a post all its own – that I can ‘see’ the project I’m about to discuss as a photography project, while my commons project I can ‘see’ more as a film; indeed, it will be the focus of my Phd.

I’ve always taken pictures of trees. My two photos published by The Guardian were both of trees, and if you look at my Instagram feed, whatever the environment, be it coastal or urban or agricultural, there’s usually a tree somewhere in a starring role. When we visited Morocco in 2018, I was as fascinated with the walnut groves and juniper scrub as I was the Islamic architecture and ancient streets.

My Hidden Corners zine for the previous module’s Work in Progress Portfolio was entirely composed of woodland shots – mostly plantation woodland. My great take-home lesson from this project was how naturally I am drawn to hidden wooded corners in the landscape, and was able to identify this attraction with the books and films of my childhood, as well as the melancholy such places evoke as befits someone such as myself who has endured long stretches of serious depression. I had felt at the time, this work was a sidestep move, largely in response to the reduced ability to travel of lockdown, but rather than get back on with visiting the commons I’d meant to – Greenham Common, the Forest of Dean, Runnymede Meadow – I’m keen to pursue this line of inquiry.

I’m keen to create as my Final Masters Project a body of work studying woodland which appears in or has influenced well-loved children’s books. Having grown up close to the Ashdown Forest, better known as Winnie-the-Pooh’s Hundred Acre Wood, this keeps the project’s personal connection. But it’s also something I can see would have a broad appeal. To begin with, in response to the climate crisis, and intensifying during lockdown, local green space and nature across all media, are enjoying considerable public attention, and the destruction of woodland, whether for HS2 or at the hands of the Amazon’s illegal loggers, is a major concern for many. In addition, children’s literature enjoys considerable cultural prestige in the UK, which has produced many of the world’s best-loved works, and is deeply connected with a sense of landscape and nationhood. A book that gathers together, in words and images, woods that many have loved without ever visiting would seem a strong candidate for publication. I also have some quite useful connections to promote this, not least the novelist, reviewer of children’s books for broadsheets and nature-lover Amanda Craig, who I have in mind to write an introduction.

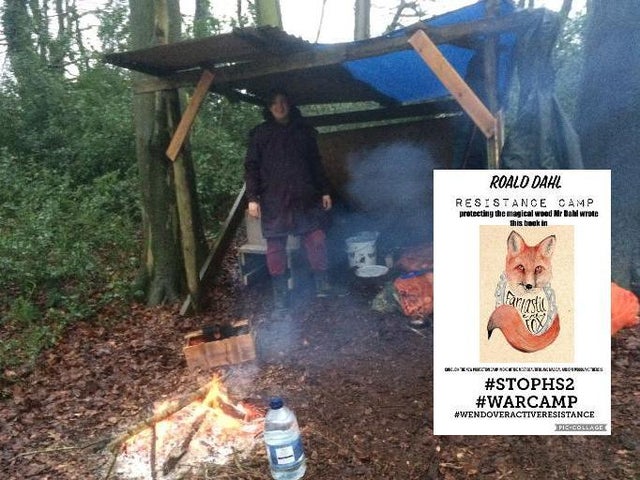

It’s important to me that the project collects a diversity of woodland from a diverse range of books. Hence I’m keen to track down the Gruffalo’s deep dark wood just as I am Enid Blyton’s Enchanted Forest. I also want to acknowledge the threats to woodland, already depicted in Colin Dann’s Animals of Farthing Wood (a housing estate in the middle of a book of woodland images would strike quite a strident note), and it’s fascinating, desperately sad and oddly fitting that half of the ancient Jones Hill Wood, which inspired Roald Dahl to write Fantastic Mr. Fox, is being destroyed to make way for HS2. Other woods already identified are Puzzlewood in the Forest of Dean (Tolkien’s Mirkwood AND Rowling’s Forbidden Forest), Wytham Woods (Horwood’s Duncton Wood), Bisham Woods (Graeme’s Wild Wood from The Wind in the Willows) and Hampstead Heath (the lampposts of which inspired Lewis to write The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe).

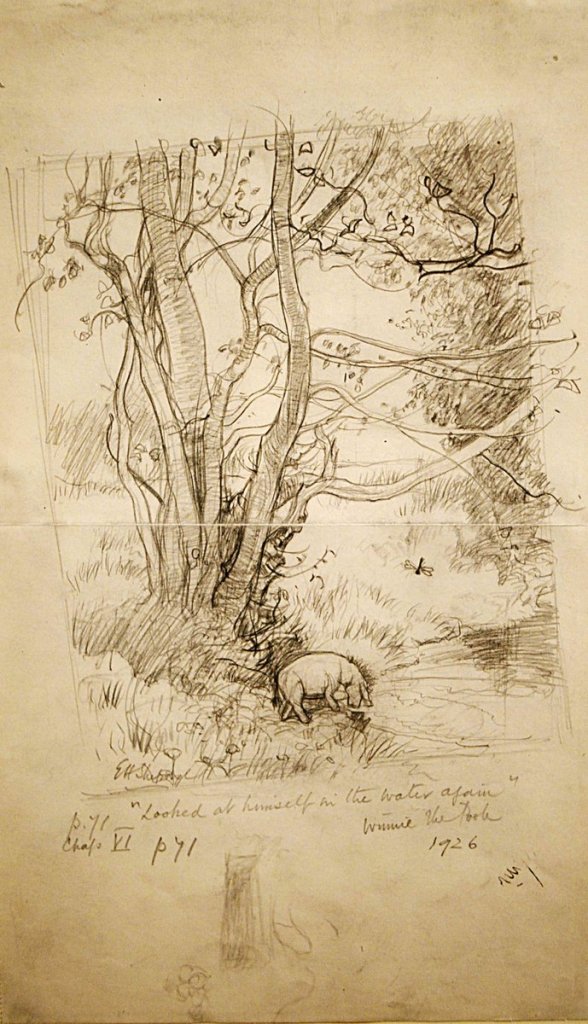

It’s also important to acknowledge that many children’s books are beloved for their illustrations. Sheppard’s depictions of the Wild Wood and the Hundred Acre Wood take particular care with trees, which often dominate the frame, and I can identify something of my own style and preferences in Tolkien’s illustrations of Mirkwood and the strange and exotic woodland of Tove Jansson’s Moominland. Thus a question of style inevitably emerges. A project photographing places used for celebrated imaginings which presenting them in a documentary, objective style would, to me, miss the point. Anyone can track down these places via Google, after all. Rather, I would prefer to use both the places and the stories to which they are connected as the jumping off point for my own imaginings. We none of us read a story in quite the same way, and our own memories, experiences and temperaments find expression when we apply out imaginations to a work of fiction. I would thus create, essentially, my own illustrations for these works.

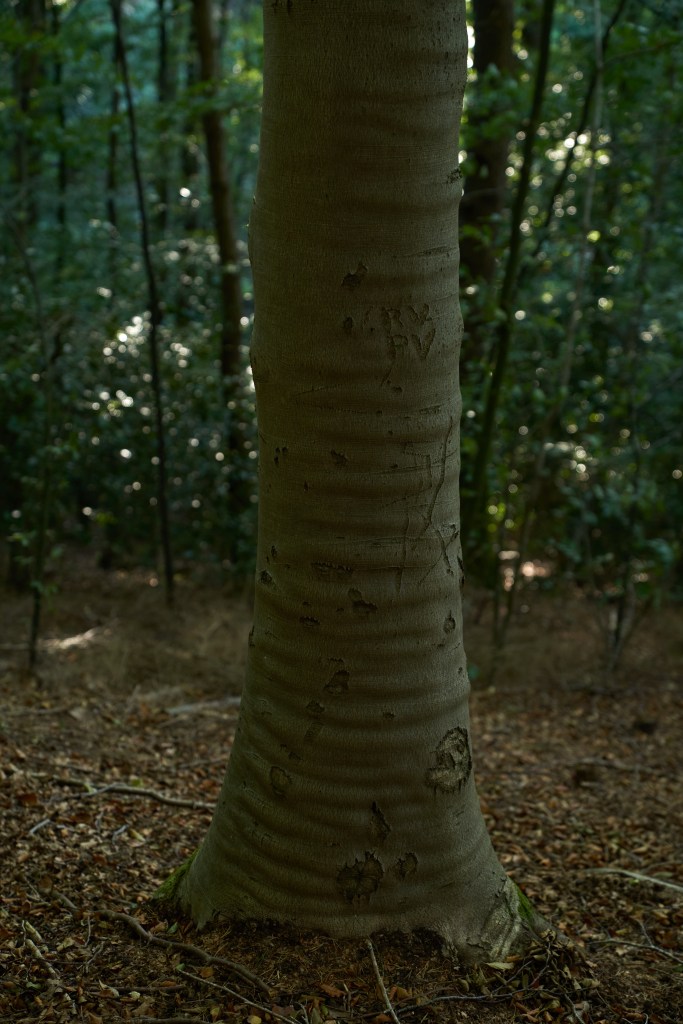

Different photographers see trees in different ways, and trees being such huge things, there are many ways of seeing them, from distant picturesque shots of a wooded ridge, to a close up abstract of bark. I increasingly find trees strange, alien things, and love them no less for that. Their bark can take on fleshy textures, as if they have appendages and orifices, and their relationship with other plants, whether parasitic or not, creates peculiar embraces and wrestling postures. The disturbed, but brilliant, imagination of HP Lovecraft has left its mark on me in this regard, and I find it hard not to relate to woodland as if it is not, in fact, responding to some alien intrusion, as does the woodland in his The Color Out Of Space. It is this strangeness which to some extent explains the enduring appeal of woodland in children’s literature – a world as foreign to children as the adult world for which it often prepares them – and so it makes sense to me to continue to capture this in my practice.

There’s a political, post-human dimension, too. It is easy to view trees anthropomorphically: like us, they stand, are long-lived, and even their limbs appear to reflect outstretched arms. But this denies trees their autonomy, their fundamental difference, and lends itself to an infantilisation which undermines respect for them as beings in their own right, something Richard Mabey proposes in The Ash and the Beech (2013). Moreover, according to Wholleben (2017), there is increasing scientific evidence that trees are to some extent sentient, albeit in a radically different way to us. Thus it makes sense to me, not to attempt to capture, or not to seek to primarily capture, whole trees, or collections of whole trees, but details, especially where those details express what Mark Fisher describes (2016) as ‘the weird and the eerie’ (see earlier posts for more on this work). So if much conventional depiction of woodland seeks to emphasise the familiar, the comfortable, the nostalgic, the restorative, I would prefer to return to that overwhelmingly found in children’s literature: woodland as unknown and unknowable, forbidding and full of possibility. And over the course of this module, rather than explore a specific woodland – although I intend to visit Stoke Woods often, a few miles from my home – I want the trees themselves to be the subject of my practice.

Fisher, Mark. 2016. The Weird and the Eerie. London: Repeater.

Mabey, R. 2013. The Ash and the Beech: The Drama of Woodland Change. London: Vintage.

Wholleben, P. 2017. The Hidden Life of Trees. London: William Collins.