If my photography is a way of ‘thinking-through’ and expressing ideas about registered commons, and if I’m drawing on sensory research as a methodology to do so, then what is the theoretical basis for my evaluation? This is an ongoing question, one begun during my film Masters, when I drew heavily on environmental psychology. Sensory ethnography uses both film and photography as practice-based research, is deeply influenced by phenomenology, and takes as a central concern people’s relationships with space by making use of some key cultural geographers (Pink, 2015). I briefly engaged with this area of research in my Masters dissertation film, and am now deepening my knowledge of it, starting with the work of Doreen Massey, and will be continuing through the work of Tim Ingold and Yi Tu Fuan. Massey was herself involved in interdisciplinary work, including with filmmaker Patrick Keiller on his influential essay film, Robinson in Ruins (2010) which drew knowingly on the traditions of landscape painting and photography; this was one of the last projects she was involved with prior to her premature death.

Massey defines space and place as distinct but indivisibly connected concepts (2006). Space, she sees as ‘the product of interrelations’, ‘the sphere in which distinct trajectories coexist’ and ‘always under construction’; ‘relations’ here are ‘understood as embedded practices’. It is thus constantly unfolding, unpredictable and full of the unexpected. Her model is thus a fundamentally political one – describing ‘the realm of the configuration of potentially dissonant (or concordant) practices’. Massey also argues that time and space are only divisible in the abstract, that ‘time unfolds as change [and] space unfolds as interaction’, especially social interaction.

Place, on the other hand, is where the trajectories and interrelations become ‘thrown together’, and equally where they fail to do so, held together by sets of ongoingly contested rules resulting from the ‘throwntogetherness’ of these trajectories and interrelations. Place is also constantly unfolding, hence it is both temporal and spatial, hence one cannot return to exactly the same place; attempts to enclose place in order to render it static is the basis for dangerous conservatism, but also poses difficult questions for heritage and conservation organisations. Doing so necessarily arrests many of the trajectories which constitute place. Rather, place is a negotiation between trajectories which are ‘sometimes ridden with antagonism’, and socially ‘places pose in particular form the question of our living together…the central question of the political’. Place formation can also require a more or less rigidly constructed ‘we’ or sets of ‘we’.

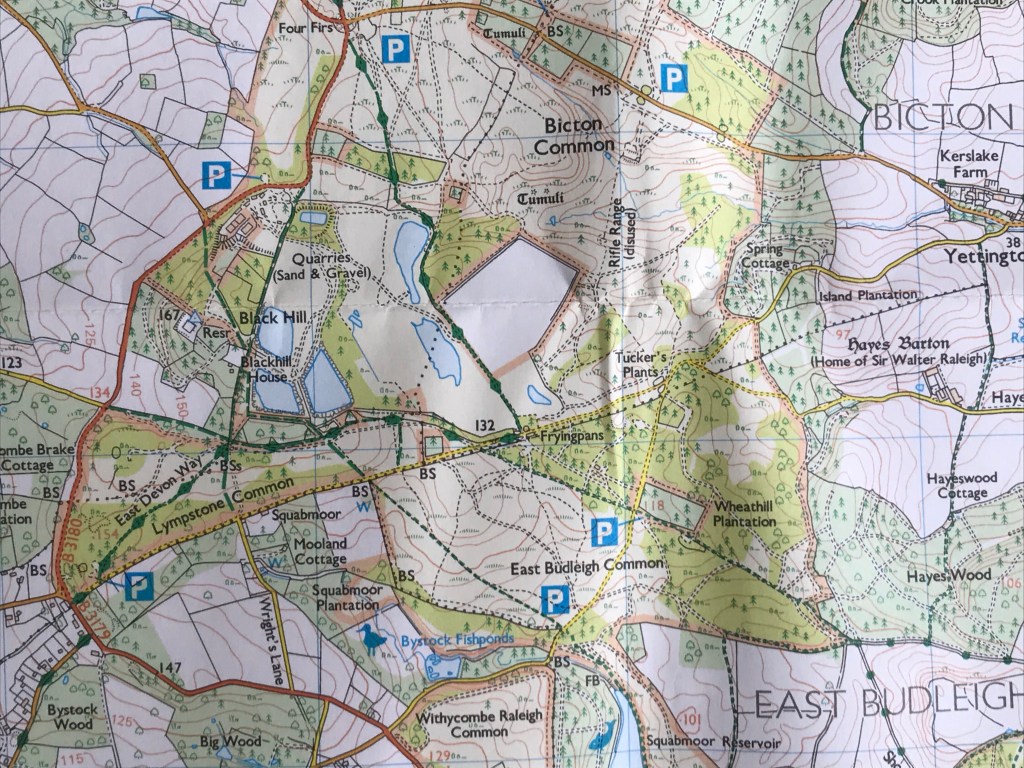

So what does this have to do with common knowledge? First, it describes perfectly the two ways I approach my practice, as ways of engaging with the Pebblebed Heaths as space and as place. The Pebblebed Heaths first became known to me as places. They are held together by sets of rules which name them, are written into law, are written onto maps. Commons are a particular type of place and when I first visited in 2008, I mapped my understanding of those rules, many of them unexamined and cultural, onto my experience of being there. I have chosen commons because I believe there is much to be learned about such rules and their physical, psychological and phenomenological manifestations, especially the historic and unfolding politics and conflicts which shape them via different constructions of ‘we’. These rules and conflicts – signs of enclosure, and of controlled burning, for example – are the markers, if you like, which plot any walk I take through the commons. My examination of the heaths as places, then, is akin to working as a hunter, or a farmer, with distinctly formed intentions informed by my understandings of the commons as places. By hunting evidence, or nurturing its eventual appearance through farming, of the various conflicts and rules which construct the heaths as places, I am experiencing and representing them as a ‘throwntogetherness’ of trajectories. I am seeking out evidence.

On the other hand, to experience anywhere solely as place is limiting, and to interrogate it critically one must also consider it as space, to tease apart the trajectories which form it. Doing this requires a loosening of intent, an openness to the happenstance and unexpected, as described by Massey, and this is precisely what most of my shoots are like: impulsive, aimless wanderings chasing after momentary fascinations and whims, and embodied experience which lets me be led by aesthetic and emotional response rather than hard-nosed wishes to represent as Rancière (2014) might put it (more of this in another post). This is when I am a gleaner, that is to say, most of the time. It is in doing so that I encounter the multiplicity of trajectories, including those excluded from the commons as closed ‘place’ – the fly-tippers, and the graffiti artists – as well as the non-human trajectories of ecological change – the ceaseless passage of water, the willows in bloom. Rather than seeking out evidence for the heaths as a place, and thus dealing with place in the abstract, I am becoming entangled in the heaths as space, and thus dealing with them in the particular, physical and as embodied experience.

Both approaches complement one another; a quick email to the site manager about a freshly-gleaned trajectory lets me examine it in light of it being included or excluded from the heaths as rule-bound places. An intentional set of rules about, for example, military exclusion areas, gives me an emplaced starting point from which to begin exploring space. While the writing for this project deals more with the heaths as places, freighted as they are with facts, they are loosened by the absence of hard context in many of the images; using text more playfully and spatially is, perhaps, something to explore further at a later date.

Deranty, J. 2014. Jacques Ranciere: Key Concepts. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Massey, D. 2006. For Space. London: Sage.

Pink, S. 2015. Doing Sensory Ethnography (second edition). London: Sage.