It might seem like a bit of a cheat, but I’m reposting a forum post here, as I can’t think of anything more pertinent to where I’m at in my practice right now. This week has been absolutely on the money for me.

This week’s topic could not have come at a more apt moment for my work. Following feedback from both Jesse and Steph at last week’s symposium, it’s clear that my work is currently weighted too heavily towards aesthetics at the expense of communication. This is something I’ve been wrangling with for some time, as on the one hand, I get great pleasure and satisfaction from the formal process of composing a well-balanced and executed image, while on the other, wishing to convey the deep politics and complex histories of registered common land. These aren’t incompatible, but this demonstrates how uneasy is the partnership between aesthetics and message. I’ll get to my images later in this post.

I’m looking at two interconnected bodies of work: first, Elliot Porter’s The Place No-one Knew (1963). Porter was an associate of Ansel Adams, a fellow campaigner in The Sierra Club, and a trailblazer in the use of colour. I’m a great admirer of his work on a formal and technical level, and because his work powerfully communicates sense of place through abstracts, something central to my own approach. He’s been a big influence on my work.

The Place No-one Knew was created to raise awareness of the imminent flooding of Glen Canyon, Utah, to create Lake Powell. A copy was sent to the president. The effort failed in the short term, but as so often, the awareness raised helped mitigate and slow down the ongoing flooding of the US South West’s canyonland for hydroelectric schemes.

So far so good. However, Porter, like Adams, was deeply influenced by a very white middle-class form of conservationism – indeed, this is still a huge problem for the conservation movement, as demonstrated by the paucity of diversity in Extinction Rebellion – although this an issue specifically being addressed within this dynamic and vital movement. Porter’s effort thus spoke to a specific audience – and on behalf of others without consulting with them first. Though remote, Glen Canyon was, in fact, already well known to hikers, fishermen, and a small local population that included Native Americans. This group, while appreciating Porter’s efforts, were nevertheless furious, not least at the name of the book.

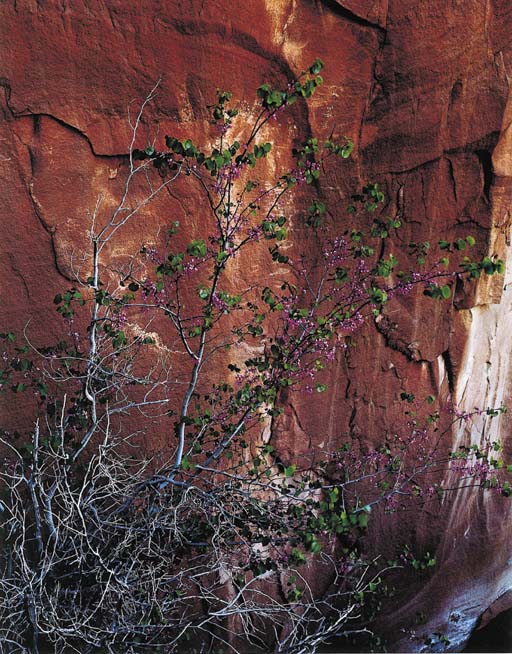

So we have Porter’s unique vision. It IS glorious, but it’s highly individualistic, and that becomes a problem when it’s married to politics. The work is, frankly, a bit TOO glorious. It might evoke a sense of place, but it does not evoke a sense of uncertainty or danger. The images are, in other words, and in spite of the accompanying essay, devoid of context (something picked up on by both Jesse and Steph in some of my own). In other words, Elliot has let aesthetics get in the way of his message. The very beauty communicated so effectively and intended to instil concern and galvanise action, ends up soothing, reassuring. Glen Canyon becomes no place at all, just another site for Porter’s work, and in that case, this suggests an abundance of glorious places for glorious work. The aesthetics anesthetise.

Drowned River: The Death & Rebirth of Glen Canyon on the Colorado is the second project resulting from a collaboration between Mark Klett, Byron Wolfe and environmentalist, journalist and art critic Rebecca Solnit. It takes Porter’s work as a starting point, respectfully but critically, and uses it to explore Lake Powell as the climate-change-driven receding water levels reveal Glen Canyon once more. The work is no less aesthetically glorious. The colours are more mute, but that’s more to do with the different technologies and tastes of each era. Klett and Byron pick up on abstracts, just like Porter, and their framing is clearly influenced by the original work. It is a celebration of a landscape and a brilliantly-executed communication of place, even if it’s quite a weird place.

Unlike the standard essay-then-images of Porter’s work, Solnit’s essay flows through the images, creating a dialogue with them, providing the contexts of climate change, critiquing Porter, but also revelling in the experience of being out exploring. There being a notable lack of prominent female ‘landscape’ photographers, having a female voice is part of the strength of the project. Both images and text situate the collaborators throughout the work, and this enhanced subjectivity, and that this is a collaboration both disrupt the individualistic vision of The Place No-one Knew. In doing this, the viewer is encouraged to develop their own relationship with the place; the observers are in this way part of what the viewer is able to observe, rather than Porter’s direct communication of a unique viewpoint. This engagement helps develop agency, and an active viewer is more likely to feel prompted to act than a passive one. The socio-political and historic context of place is also communicated through the images, though without didacticism. Hence litter, cracked mud and vapour trails are stark reminders of environmental destruction, while abandoned picnic tables, boats and closure signage remind of the cost of the receding waters to local communities. In this way, the viewer gets the impression of being a fellow traveller to the leading edge of catastrophic climate change and the novel landscapes it is already creating.

I took on board what was said to me by Jesse and Steph, and with this in mind, went looking more specifically for the military traces at the Pebblebed Heaths. Aesthetics have remained important – and there are here images taken just to communicate a sense of place – but a meticulous, critical eye keen to communicate context was also something I had in mind. I’m still sorting through these images, but below are a few.

Klett, M., Solnit, R., & Wolfe, B. 2018. Drowned River: The Death & Rebirth of Glen Canyon on the Colorado. Santa Fe: Radius Books.

Porter, Elliot. 1963. The Place No-one Knew. San Francisco: The Sierra Club.