I was out shooting yesterday at Mutters Moor, a sliver of common along an East Devon ridge, when I came across a shiny white Land Rover and a picnic table groaning with thermoses, bottled water and snacks. The table commanded a stunning view, new to me, up the coast towards Exmouth and on to Torbay. It’s a view so stunning, so I was told by the Land Rover’s keeper, it’s even got a name: The Queen’s View. The keeper explained he was awaiting a group of off-roaders in 4X4s off for a corporate day out – his business. After chatting a while, I took in the view and went my way.

This would have been a great photo op. It’s incongruous, political (considering the ongoing battles against off-roaders in the Lake District) and would have been aesthetically interesting. However, as I went my way, it occurred to me I never even thought to include what I’d stumbled across in my walk, in the way I’d included logging an hour or so earlier. This is partly because I’m still very shy of asking to take people’s photos, however much reassurance I might have had from people over the years. But I think there’s something else going on. I think, for what I’m trying to achieve, people are a distraction.

The influential theorist of film sound, Michel Chion, argues that whenever a human voice appears in a soundtrack, it without fail attracts attention to the extent where it instantaneously becomes predominant. I’ve argued previously, also referring to film, that the appearance of people into landscape has an analogous effect, and used this phenomenon in my film, Strands, by allowing the audience time to experience an unpeopled landscape before people enter the frame and after they leave it. This was intended to allow the audience both to ‘dwell’ in the landscape in sensory terms and to experience it as mediated by people connected with it in narrative terms.

The temporally-fixed frame of stills photography does not allow for such flexibility, but neither does it make such flexibility impossible. The work of, for example, Simon Roberts, envisions landscape in a very human, narrative way by including activity, even when taking up a minute portion of the frame; it is about landscape, but it is even more about specific people’s relationship with their landscape, as demonstrated in series titles such as We English. When faced with his work, which I love, my initial response is to wonder who these people are and what they’re doing, before beginning to see their relationship with the rest of the image.

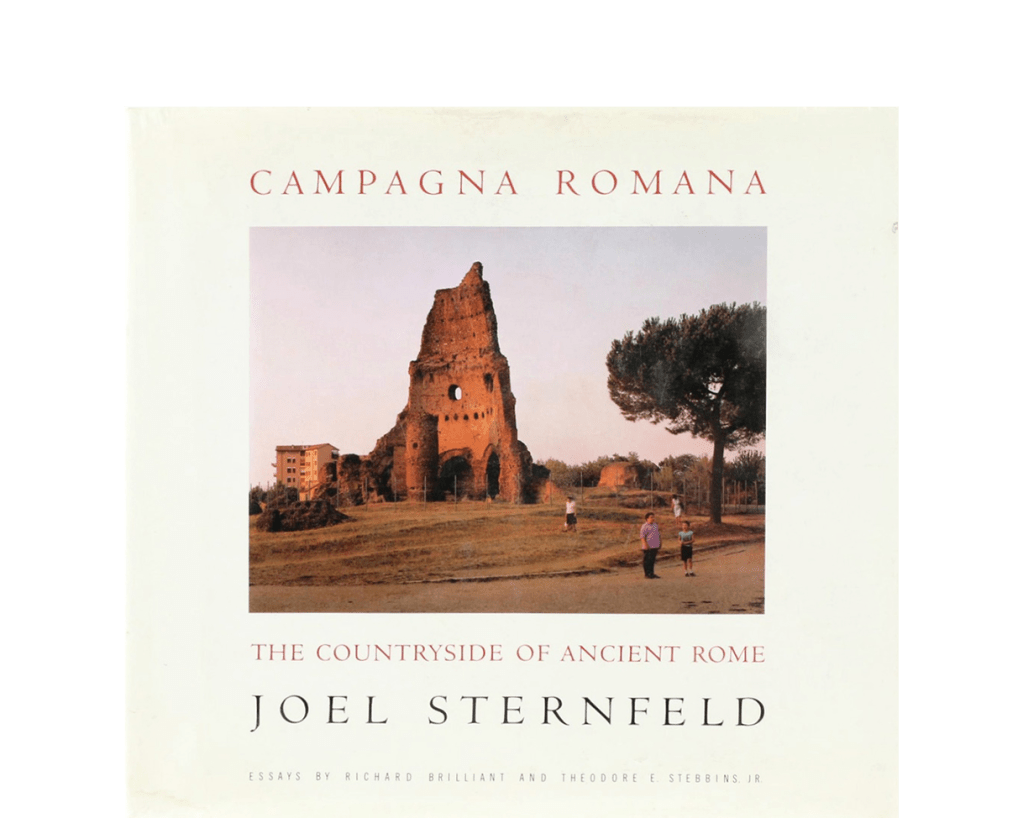

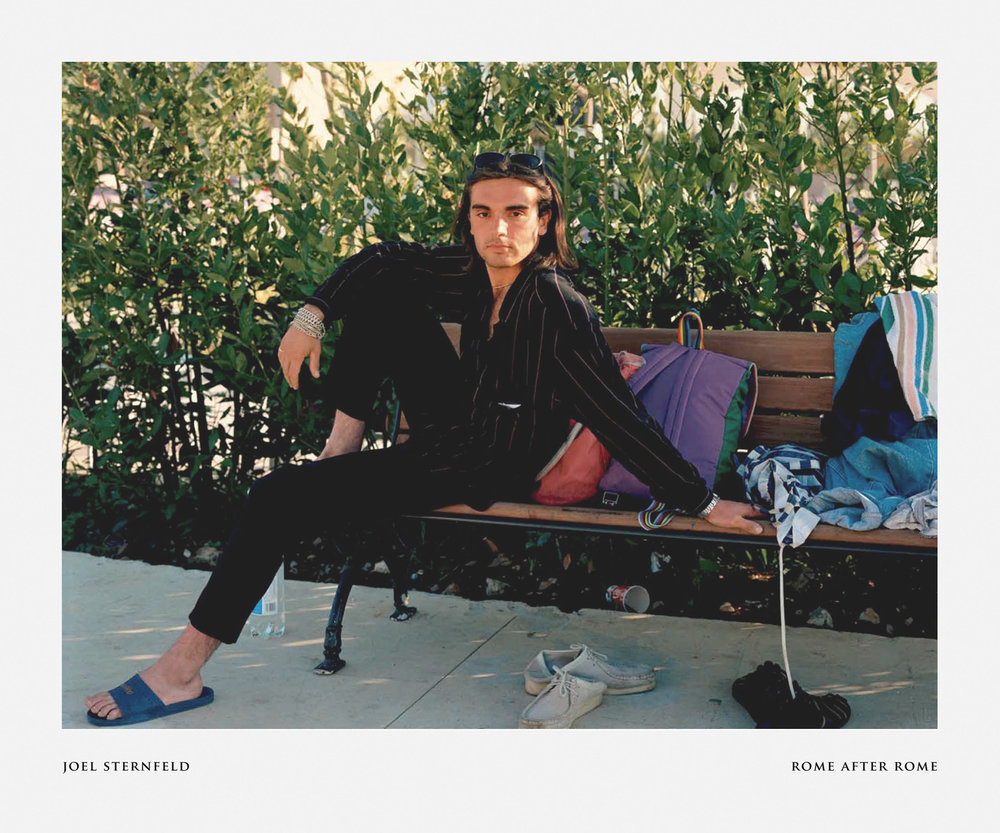

Another strategy is to interlace unpopulated landscape shots with portraits or documentary images. This was Joel Sternfeld’s approach in Campagna Romana, which has scant, slightly surreal but poignant portraits in amongst the shots of the remnants of ancient Rome taken over several years. It’s an exquisite series that allows for a sense of discovery of this extraordinary landscape that extends to a map at the back. Last year’s Rome after Romerevisits and reenvisions this series, richly updating its reproduction but also including far more portraits to the extent where portraits follow one another. The book is, deliberately, much more about the people: the landscape becomes theirs, rather than as previously, they appearing as a part of their landscape. While no less successful as a book, the sense of immersion is gone, and one gets the sense of peering around the portraits to see their landscapes. This difference is demonstrated effectively by their two different front covers.

People are very much a part of my commons project. Commons are given their characteristics by human agency, whether conservation, history, leisure or economic usage, or – especially – legal status. I want to explore these dimensions in my project, and I also want to explore the different sensory ways in which they can be experienced – what it feels like for people to be on a common. I want my project, as with Strands, to be an immersive experience. I want viewers to have a degree of agency, to be able to develop their own connections and explore the landscapes presented for themselves, partly to give them space to reflect on their own experience of commons, and I believe my intentions could be at odds if I included people visually in this project. So, had I included a portrait of the man with his Land Rover, or his assistant at the picnic table, even if relatively small in the frame against the magnificent backdrop of The Queen’s View, the image would become primarily about off-roading, and the meanings to be drawn from it, and about The Queen’s View as a cultural rather than sensory experience. Nothing wrong with that, of course, just not my intention.

It has long been my intention to include writing in my work, and through leaving the visual ‘channel’ unpopulated but populating the textual ‘channel’, I think a balance could be struck: ultimately, it’s the viewers choice how to interrelate text and image and all kinds of interrelationships can be explored through formatting, something I’m investigating presently. But that’s something to discuss on another occasion.

Chion, M. 1999. The Voice in Cinema. NYC: Columbia University Press.

Roberts, S. 2009. We English. London: Chris Boot.

Sternfeld, J. 1992. Campagna Romana.NYC: Alfred A. Knopf.

Sternfeld, J. 2019. Rome After Rome. Göttingen: Steidl.